A Short Story, September 2025

You can’t go faster than 35 miles per hour. It’s too dangerous. The human body can’t survive the stress of going that speed.

That’s what everyone told me when I arrived back in 1773 – old Colonial America – in my time machine. I tried to explain to them that my time machine could go thousands of miles per hour before it crashed.

George Washington laughed in my face. John Adams said I was a dangerous madman who should be ran out of town before he hurts somebody. Thomas Jefferson said, “well, maybe.”

So I set out to prove the doubters wrong. Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were the only ones who believed me. Patrick Henry gave a big speech about how anyone who tries to go even over 20 miles per hour would die. We all know that, he said because the math shows that someone who falls just fifty feet is traveling 20 miles per hour, and that’s a high enough fall to kill. I tried to explain that, as the old saying goes, that it’s not the fall that kills, it’s the sudden stop, but I don’t think they got it.

I knew I probably would never be able to fix the time machine. And if I were, it would take decades of accelerated industrial development before I could even make the tools I needed. So, for starters, I thought I might invent the train locomotive. It would only be about thirty years ahead of schedule, really, and might give the early American economy a big jump-start.

So with Franklin’s facilities and Jefferson curiously looking over my shoulder, I started work on the train. I built it in an old barn outside Philadelphia, while Robert Morris, some rich banker from Philadelphia, started construction on a nineteen mile run of train tracks to Wilmington, Delaware. According to Franklin, Robert Morris was the richest man in the colonies, and he didn’t mind when the naysayers called the railroad “Morris’s folly” and stuff like that.

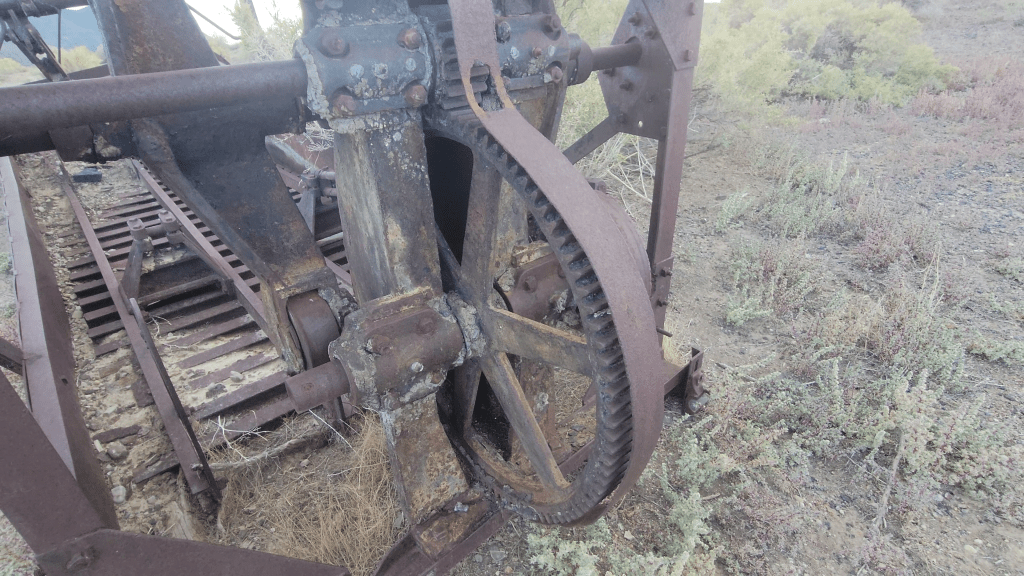

It took three years to get the train built and working. None of the parts existed, even the iron they had at the time was inadequate for the job. It required building a new smelter and coking plant and drill presses to cut out the parts – three decades of industrial development compressed into a few years, just because of the knowledge I brought back.

On the day we were finally ready to test the train, most of the city of Philadelphia turned out to watch us. Many brought picnic lunches. I think they were curious to see what someone who died from going to fast looked like. Franklin and Jefferson were both scientifically-minded, and had tried and failed to convince the people that this could work, but nobody seemed interested in listening. So as a show of confidence, Franklin decided to be the engineer and Jefferson was the fireman.

I watched with the crowd, a few of whom were curious, but most were insistent that the two men on the locomotive would be killed, or that they would stop the train once they realized the stress on their body from going that fast was too painful.

Jefferson stoked the boiler. Franklin released the brakes. And the locomotive was off. It picked up speed quickly. The crowd gasped collectively, and Franklin waved merrily as he zipped past. Jefferson kept a more serious face, but it was clear he was enjoying himself, too.

After they had passed and were on their way to Trenton, the crowd remained, discussing. Some thought it was a hoax, some thought they need a better way to measure speed. No one was ready to have their mind changed yet.

Less than an hour later, the steam engine roared back into view, with Franklin triumphantly holding a copy of the Trenton newspaper and waving it at the crowd. By that timing, they must have averaged almost forty miles per hour.

The crowd cheered as the steam engine passed, but the cheers turned to screams as it disconnected from the rails and flew wildly to the side of the tracks. It plowed over at least a dozen onlookers and Jefferson and Franklin were thrown a hundred yards down the tracks.

After some investigation, I found that the crash was probably due to a broken rail causing the locomotive to disconnect. Franklin was buried in Philadelphia, Jefferson’s body was returned home to Virginia. Pennsylvania and Virginia are looking for replacement delegates to the Second Continental Congress this July.

You can’t go faster than 35 miles per hour. It’s too dangerous.