The struggle between reason and experience as a means for discovering truth is a problem as old as philosophical inquiry and a key to the story of civilization. The technological and economic development of the modern era is sometimes attributed to an Enlightenment solution to these problems of epistemology, yet the nature of empirical data remains unchanged and reason remains subject to errors. Reason is the most error-prone area in our epistemological toolbox and often the flaws we see in empirical data are often more a function of rational interpretation than of flaws in our senses themselves.

The process of discovering the errors and shortcomings of reason was a major part of building up the study of philosophy, and the story of the classical period was that of maximizing reason while setting up empirical and logical checks against its errors. Although Plato, Aristotle, and other thinkers both ancient and modern attempted to place checks against the biases and errors of our own reason, these checks failed in multiple ways and progress in technology, commerce, the arts, and science were slow until roughly the early modern period. I argue that the most successful check on reason that also allows knowledge to progress is the pragmatic testing of ideas distributed across free individuals, a process I term “anarchic pragmatism.” This is what began to occur in the early modern period as a middle class begin to develop to test theories pragmatically.

Contents:

- The Shortcomings of Reason

- Metaphysical Pursuits

- Reason and “Proofs”

- The Need to Place Checks on Reason

- Is the Knowledge of Pure Reason Empirically Necessary?

- Empiricism, Reason, and Science

- Metaphysics and the Modern Era

- Uncertainty of Scientific Paradigms

- Pure Reason in Science

- From Physics to Conspiracy Theories

- Is Experience Still Uncertain?

- Everyday Pragmatism and Pragmatic Philosophy

- Is Science Pragmatism?

- A New Pragmatic Approach

- The Process of Anarchic Pragmatism

- The Anarchic Pragmatic Relationship Between Arts and Values

- Technology Vindicated by Anarchic Pragmatism

- Practicality, Expertise, and the Economy

- The Boundaries of Anarchic Pragmatism

- The Responsibilities of the Anarchic Pragmatist

The Shortcomings of Reason

Before laying out a theory that attempts to solve some problems related to our use of reason, it is important to identify exactly what the shortcomings of reason are, previous attempts to solve them, and why experience in the sense of empirical sensory data is not adequate to correct reason’s errors. Epistemology is taken for granted outside philosophy. Many scientists are convinced that “the scientific method” is not only capable of solving all problems in science, but also is capable of answering the nonscientific questions necessary to live as a society or make individual decisions of how to live. Outside the scientific community, most people are content to solve their problems with common sense realism, and to insist that the conclusions they make with their reason with input from their everyday sensory experience represent the world as it is and are beyond dispute.

We must therefore begin with the proposition that reason, the faculty that allows mathematics and sets humans apart from the rest of biology, can be fooled. Socrates’s observation that “all I know is that I know nothing” is both a statement of this as well as an example of it, as the paradoxical nature of this idea indicates that the mind is holding two contradictory ideas:

1. I know something (that I know nothing)

2. I know nothing

We recognize this quite easily as a paradox, but some paradoxes are more difficult to recognize or to find the error that makes their logic faulty. Take Zeno’s famous Paradox of Motion, which seems to prove the impossibility of motion. Zeno argues that in order to reach a given point, one must reach the halfway point between that point and one’s origin. But to reach the halfway point, one must reach the point halfway between the halfway point and the origin. And on and on an infinite amount of times. One must travel an infinite number of half-journeys between the two points, but it is not possible for anyone to do an infinite number of things. We can therefore reasonably conclude that it is not possible to travel from one point to another.1 To a mind that had never experienced motion and yet had some idea of it as an abstract, this would seemingly prove that motion in space is as ridiculously impossible as motion in time. To those of us who have, in fact, moved many times before, such logic is obviously ludicrous, so we formulate some conception of motion in which the task of moving by halves does not apply. We have here a reasonable argument for an unreasonable proposition, which we debunk because it contradicts our everyday experience.

Metaphysical Pursuits

While our individual sensory experiences almost surely reflect some kind of underlying reality and can give us some information from that reality, few would argue that experience, or empiricism, is reality in and of itself. There must be some kind of fundamental underlying reality, and the way to reach it is probably through reason. After all, when we say that our experiences reflect underlying reality, we are making a judgement that is not justified by our experiences. This search for the fundamentals of reality aside from empirical experience is metaphysics in its basic form. Where fundamentals of reality make predictions, we move into the realm of physics.

Ancient philosophers of physics and metaphysics had an incredible ability to come up with outrageous theories and justify them through reason. From the classical system of the elements; earth, air, fire, water, and sometimes aether; to Thales of Miletus’s assertion that in essence all of these were forms of water and that the earth itself floated on water, to Heraclitus’s opposite assertion that all things are derived from fire, or “fiery aether,” thinkers tried to figure out what the “true form” of reality was.2 Many ancient Greek philosophers threw their hats into the debate of whether all things in the physical world were constantly changing and that change was the fundamental characteristic of matter versus the opposite contention that change is an illusion, because a change in a thing implies that there was a time when the changed version of the thing did not exist.3 Plato’s famous Allegory of the Cave alleges that this reality is just a shadow of the true world of the forms, and an outside, non-material, pure state of being reality gives the physical world its shape.4

Reason can justify such theories as well and even if future thinkers can make rational arguments against them, such arguments might also be at risk of being overthrown by some future argument. More commonly, people hear such arguments, combine them in their heads with other arguments they have heard, the mental shortcuts they take, the premises and definitions they assume, and their emotional attachments to the issue, and come to completely opposite conclusions. This makes the problem of knowledge even more complicated than just that of uncertainty.

Reason and “Proofs”

Since the classical era, certain theologians and religiously oriented philosophers have asserted various proofs of the existence of God, which rely on reason. These include the teleological argument, which, simply put, asserts that the complexity and functionality of the world imply a design, and if there is a design there must be a designer. But in addition to this fairly reasonable, if flawed, proof is the more outrageous ontological argument in its various forms. Ontological arguments have several variations from eminent philosophers such as Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Kant, and Gödel, and have been brain-twisters to countless others. The eleventh-century theologian Saint Anselm of Canterbury formulated perhaps the most understandable version of the argument, as follows:

1. By definition, God is a being than which none greater can be imagined.

2. A being that necessarily exists in reality is greater than a being that does not necessarily exist.

3. Thus, by definition, if God exists as an idea in the mind but does not necessarily exist in reality, then we can imagine something that is greater than God.

4. But we cannot imagine something that is greater than God.

5. Thus, if God exists in the mind as an idea, then God necessarily exists in reality.

6. God exists in the mind as an idea.

7. Therefore, God necessarily exists in reality.5

Even many religious individuals can see that there is something tricky going on with the Ontological Argument that does not quite follow, and yet Bertrand Russell, the twentieth century’s preeminent logician and leading atheist, wrote in his autobiography that he once was walking down the streets near Cambridge when he suddenly exclaimed: “Great God in boots! – the ontological argument is sound!”6 Russell observed that it is much easier to dismiss the ontological argument as wordplay and useless riddles than it is to exactly identify exactly where the error is.7

Logical proofs of no god are often as if not more untenable than the proofs of god, but the passionate atheist will often accept these arguments just as well as the religious person will accept what supports their ideas. The “problem of pain,” which has often been a problem for devout theologians to solve, convinced Voltaire that god does not benevolently influence the world because such a god would have prevented the 1755 earthquake in Lisbon. This argument has been taken further to claim that because there is pain in the world, there is no god. Most people can logically agree that a god who is defined as completely omnipotent to the point of being able to create logical contradictions and is also omnibenevolent would stop pain, but there is disagreement across the faithful about what omnipotence means. There are many conceivable limits on the power of god that would lead to a flawed world, the best known of which is that he cannot cancel the effects of sin. Whatever the reason, or even leaving the reason unknown, it is quite reasonable to say that nothing proved. A determined enough atheist, however, will consider this negative proved. There is a simpler argument used for atheism as well:

1. If there is a god, there must be evidence of a god.

2. There is no evidence of god

3. Therefore, god does not exist.

Plug anything not yet discovered into the place of god, and the same logic holds. Is it the case that the magnetic field did not exist until we discovered it? What about dinosaurs? Or black holes? Or any other incredible discoveries humanity might achieve? And what counts as evidence? Why does the teleological argument not count? These are simplifications of the arguments both for the existence of god and against, but the fact that they both seem logically acceptable and yet contradict each other shows that reason combined with experience is so far inadequate to make such big determinations.

This is not to say that “logic is wrong,” only that it is reliant on the accuracy of the terms and premises that are necessary for logic to do anything useful. These terms and premises are flawed because of the ambiguity of language and the mental shortcuts that produce the premises. Our shortcut-trained brains often do not recognize when they have taken mental shortcuts or imported emotions because simplified thinking is so natural to us.

The Need to Place Checks on Reason

So how, then, do we “check” reason to keep it on the straight and narrow and assure we can trust what it tells us? This has been a problem from the earliest stirrings of philosophical inquiry, when Melissus wrote that everyday common sense creates contradictory and irrational notions.8 His argument was an attack on both the validity of empirical data and the simple application of reason to experience. In the same era, Parmenides asserted that the reason people held false beliefs was that they allowed themselves to believe contradictions.9 Non-contradiction to Parmenides was a key criterion of truth, and this idea is vindicated by formal logic and mathematics. Even the most hardened skeptic would be reluctant to say that “A is B and A is not B” might be possible and they cannot reject it for certain.

It became clear by the classical period that “common sense realism” was limited in its inability to address complex problems and that its reliance on mental shortcuts can produce incorrect results. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave further asserted that common sense, everyday knowledge was inadequate to know the world “in itself,” i.e. the fundamental world of the forms. Before that, Socrates gained his reputation as a “gadfly” for poking holes in the common-sense realism versions of concepts like justice and virtue and piety held by the most learned men of Athens. Socrates was not content with just a list of items that fall underneath each of these categories, as making lists shows that the concept is not justified on a fundamental logical level but instead is chosen arbitrarily by the learned list-maker by combining their own opinions with the cultural norms of their time.10

Is the Knowledge of Pure Reason Empirically Necessary?

In the eighteenth century, Immanuel Kant transformed epistemology by arguing that philosophy ought to abandon the quest to know the world “in itself.” The pursuit of this objective was responsible the proliferation of metaphysical theories, and because metaphysical endeavors are reliant on pure reason and have no participation in “practical reason,” or the everyday synthesis of reason and empirical data, they will be always disconnected from verifiable empirical data. His Critique of Pure Reason argues that there can be no “synthetic a priori knowledge,” or knowledge derived purely from reason. Synthetic a priori knowledge is that which is created solely in the mind and therefore cannot be justified empirically.11 If knowledge cannot be tested, than how do we know it is true? How do we know that the basic, innate ideas that influence our a priori knowledge are not a consequence of our evolutionary psychology, our cultural training, or just some kind of mental deficiency? It is for that reason that Kant rejects synthetic a priori knowledge in favor of that which can be empirically tested.

But how do we tell what ideas are, in fact, purely a priori? Is Occam’s Razor, which says that the simplistic answer, or that with the least assumptions, is the most likely to be correct? It may be that all of our experience which justifies the validity of Occam’s Razor is in fact a series of coincidences and misinterpretations. We might say the possibility of such a series of errors and coincidences is highly unlikely and that a simpler answer, such as that things tend to be correct when simple because simplicity is evidence of truth, is a more likely explanation because it is simpler and requires us to assume less coincidences. This is justifying Occam’s Razor with Occam’s Razor! This raises the very real possibility that certain assumptions, which are essential to the pursuit of science, come not from empirically quantifying data but from habit, practical knowledge, and even that impossible synthetic a priori knowledge.

Knowledge of virtue and reality are even more difficult to get to with synthetic a priori knowledge left out. Kant famously tries to justify a moral philosophy within his empirical framework with his “Categorical Imperative,” in which one should ask “what ought I do?”, and ask what the implications would be if this were made into a universal principle. Any formulation of the categorical imperative, will of course require an intuitive judgement in the end, meaning that some synthetic knowledge is imported.

Kant also attempts to deal with the most difficult aspect of his theory, that of mathematic knowledge. If our pure reason is so helplessly flawed, than why are mathematical judgements, a priori knowledge, so consistent, easily empirically verified, and pragmatically useful? Anciently, the Pythagorean philosopher Democrates saw impurity of reason via the influence of experience as the source of error which much better explains why mathematics, the purest form of reason has such a high level of reliability and certainty. But if this is indeed the case, then why should the rise of empiricism in science in the fifteenth-seventeenth centuries lead to greater scientific success?

This is a problem which Kant did attempt to solve, and to do so he claims that a mathematic proposition such as 7 + 5 = 12 is not merely an analytical proposition, which takes synthetic a priori conceptions of the numbers and of addition and weighs unites them. He instead claims that as humans we in fact receive our conceptions of number from experience.12 We receive outside justification of our conceptions of 5 or 7 by counting on our own fingers, and by experimenting with more and more complicated math in the world of experience. His solution remains imperfect, and it remains to each of us to analyze our minds and ask if it is it really by virtue of counting blocks that we are justified in our belief that 7 + 5 = 12.

Empiricism, Reason, and Science

The development of “the scientific method” is often simplified to being an invention of the seventeenth century by Francis Bacon and/or Galileo Galilei, though Aristotle set out how one should make inferences based on data. Scientific methods in fact very wildly across fields, though they share that common attribute of recognizing the value of empirical data. Even within the scientific framework, empirical data is still entirely subject to interpretation by reason and is often generated by experiments created by someone hoping to vindicate the ideas generated by their own reason. Theoreticians of science try to ensure that such explanations are both not self-contradictory and are simple, but these criteria import the synthetic a priori ideas that things must be consistent and simple, and therefore are checks on reason not founded on empirical data.

Simplicity and elegance have long been considered criteria for the acceptance of a scientific theory. Both the value of these criteria and the interpretation of what is considered elegant are functions of reason. These criteria can result in some wildly incorrect conclusions, such as the rejection of the Kepler’s model because the old theory of circular orbits was more simple than elliptical orbits. A circle is the most simple shape possible, so why would we reject the simple circular orbits of the planets for the more complex theory of elliptical orbits? The change was eventually made because advanced methods of astronomical observation and record-keeping showed that the circular orbits could not be conformed to the data, but before elliptical orbits were accepted there was a competing theory of circular orbits with smaller circular “epicycles.” Who is to say that an ellipse is more simple than a circle of circles? The underlying principle of circles remains in the “epicycle” model, why should it be considered less simple than that in which the fundamental principle is of skewed ellipses? It comes down to a judgement of reason that can have different results when judged by different people. In decisions of scientific judgement like this, the accuracy of reason is in question.

Similarly, Aristotelian laws of motion could easily be seen as more simple and elegant than those of Newton. Aristotle believed that rest was the natural state of matter, and therefore all things in motion return to rest unless continually accelerated by an outside force. This seems more natural, intuitive, and arguably simpler and more elegant than Newton’s almost opposite law that all things in motion remain in motion unless acted by an unknown force. Explaining why Newton’s physics can account for the tendency of everyday objects to return to rest after being set in motion requires us to another assumption to our theory: friction. In everyday life, Aristotelian physics seem to be obvious. To anyone who has traveled by aircraft, Newton’s laws of motion have great pragmatic value, though the criterion of simplicity risks rejecting them.

Empiricism can be easily swayed by the processes that select which data actually are received by the senses. Selection bias can lead to instances where the theory succeeds being judged by reason to be empirical evidence of the theory, while those that contradict the theory being deemed anomalous. Survivorship bias can cause successes attributable to pragmatic selection, or the everyday usefulness of an idea, to instead be attributed to the rationality of “the scientific method.”

The modern scientific method has very little ability to categorize uncertainty. Certain experiments express certainty as a “p-value,” which is defined as the probability, under the null hypothesis, of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed. More simplified, the p-value tells us the odds that the conclusion might be wrong due to an unlucky coincidence, but there is nothing that tells us the chances that data might be misinterpreted, inaccurate, or systematically biased by some undetected factor. These are factors that anyone interested in making a judgement of the certainty must read the research an attempt to evaluate their methodology and findings by their own judgement, with no way to easily categorize which findings might be more useful.

The science that tests how two chemicals behave together is substantially different from that which predicts a certain rise in sea levels in the next century or guesses at the approximate geographic and temporal range of Stegosaurus stenops. Looking at these three fields, we might conclude that there are three scientific methods. They share the common factors of proposing hypotheses and testing them against empirical data, but the criterion for testing and the methods for generating data very wildly across fields. Philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend’s theory of “epistemological anarchism” holds that there are no useful and exception-free methodological rules governing the progress of science or the growth of knowledge. Feyerabend claims in his provocatively titled Farewell to Reason that “there exist no ‘objective’ reasons for preferring science and Western rationalism to other traditions. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine what such reasons might be. Are they reasons that would convince a person, or the members of a culture, no matter what their customs, their beliefs or their social situation?”13 The only possible answer to his question is rooted not in more science or reason or empiricism, but rather in pragmatism or, more simply, practicality. The only reason for preferring science and “Western rationalism” is their history of facilitating useful discoveries that increase value across large populations.

Metaphysics and the Modern Era

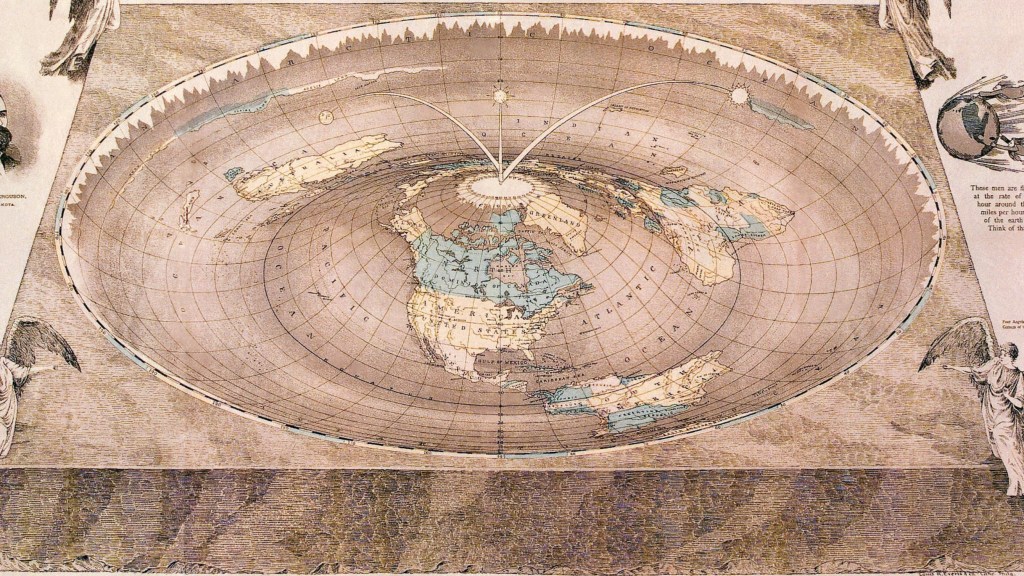

The modern era is marked by countless improvements to quality of life, technology, and median wealth across the world. This is sometimes attributed to the incredible leap epistemology took in the European sphere of influence by adopting “the scientific method.” The methods of science did improve greatly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but the core problems of epistemological uncertainty are still present in every corner of modern science. Belief in a flat earth, geocentric universe, bodily humors, and the classical elements may be mostly extinct, but at the edge between physics and metaphysics wild and untestable theories still are asserted and even widely accepted in the scientific community.

A common set of theories propose a multiverse, in which our universe is just one among an uncountable many. Such theories take multiple forms, with physicist Brian Greene identifying nine types of multiverse theories in the literature, including the “quilted multiverse,” “holographic multiverse,” “simulated multiverse,” and the famous “quantum multiverse.”14 Variations of multiverse theory are accepted by modern luminaries of physics such as Michio Kaku, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and the late Stephen Hawking. These theories bear a more than superficial resemblance to the radical metaphysical systems of the pre-Socratic metaphysicians. They may contain more mathematical elaboration than Thales’s proposition that everything in nature was based on the originating principle of water, but both theories are unfalsifiable, based in reason alone.

The same holds true for another major other emerging metaphysical theory in physics: string theory. String theory, in its current form, is more a proposal that a theory may exist rather than a theory unto itself. This naturally makes it even more difficult to falsify, as not only is it untouchable by empirical data, but it cannot even be confronted directly by logic.

Uncertainty of Scientific Paradigms

The comparatively more certain areas of relativity and quantum mechanics are constantly at risk of being overturned when the twenty-first century’s Einstein or Newton enters the picture. Newton’s theory of gravity has great explanatory power when looking at the behavior of our solar system and was therefore the consensus that guided physics for over 200 years. Modern physicist Lee Smolin points out the possibility that the understanding of the how and why of physics is always at risk of being overturned:

In 1900, William Thompson, an influential British physicist, famously proclaimed that physics was over, except for two small clouds on the horizon. These ‘clouds’ turned out to be the clues that led us to quantum theory and relativity theory. Now, even as we celebrate the encompassing of all known phenomena in the standard model plus general relativity, we, too, are aware of two clouds. These are the dark matter and the dark energy.15

Contemporary physicists tend to produce ad-hoc, difficult to falsify theories to fill in the gaps left by the “two clouds.” The dark matter and dark energy hypothesis were created to attempt to explain the fact that our current understanding of gravity and relativity do not explain why the universe expands at its current rate. Given our current understanding and our measurements of the amount of matter observed throughout the universe, the universe should be expanding a lot faster. It is theorized that there then must be a category of matter we do not understand which is providing the additional mass that is slowing the expansion of the universe. Smolin observed on this problem:

Today most astronomers and physicists believe that this is the right answer to the puzzle. There is missing matter, which is actually there but which we don’t see. This mysterious missing matter is referred to as the dark matter. The dark-matter hypothesis is preferred mostly because the only other possibility–that we are wrong about Newton’s laws, and by extension general relativity–is too scary to contemplate.16

Inventing a new kind of substance with only the properties that fit the theory to explain away the flaws in a theory is not a new practice in science. The aether was proposed by Newton as a substance that could provide a medium for light waves to propagate without exacting friction on the planets. The “fields” in which modern waves propagate are similar, in that all we know about them is the fact that certain waves propagate in them and that they can be interfered with and interfere with certain particles under certain conditions.

The physics of the modern era is focused on trying to find a “unified theory,” a single fundamental law that explains the other fundamental laws that explain all things in science. In this quest physicists have moved past the line between physics and metaphysics into a world in which theories cannot be tested scientifically or experienced empirically at all. String theory, or the possibility of a string theory, is that hypothetical underlying principle of the universe that explains everything from relativity to quantum uncertainty to the relationship of matter and energy fields. While there may be possible discoveries in that direction, physicists speculations on this subject are essentially similar to Heraclitus’s speculation that all fundamental objects and forces in the world are derived from fire.

Pure Reason in Science

The proposal of new ideas in science is still bounded by certain synthetic a priori criteria that are treated like the dogma of science. This scientific method is a check on reason by reason. Two common examples of this are the value of simplicity and the worldview of realism. A simple theory may be accepted even if it is less explanatory than a more complex one, hence the hypothesis of a unified theory. Our objective to try to find simpler theories that can simultaneously explain a wide variety of phenomena risks leading us to accept a simple theory despite its flaws.

Realism, or the idea that the outside world exists independently of our analysis of it, seems like a very common sense a priori idea. Physics must describe how the real world behaves without the influence of humans. But the “observer effect” in quantum physics shows that this dogma may in fact be holding back science.

Simply put, the observer effect is the theory that observing a phenomenon can change that phenomenon. The observer effect has been tested many times through the double slit experiment, which shows that the presence or absence of an observer changes the behavior of a particle. In the experiment a series of particles, photons, electrons, atoms, even certain molecules are fired at a screen one at a time with a barrier with two vertical slits between the source of the particles and the screen. When light or any other wave passes through such a barrier the interference of the waves creates a series of vertical lines on the screen. When particles are shot one at a time through the same double-slit barrier they should form two lines, as they are not interacting with other particles. The experiment finds that particles shot one at a time still behave as if they were interacting waves. When experimenters try to observe how the individual particles are behaving, they create a double-slit pattern like they should once again. When the particles are not observed, they once again act like waves. The mere presence of an observer changes their behavior from that of a particle to that of a wave.17

Taking into consideration the possibility of an observer effect, a simple thought experiment may bring the usually unquestioned premise of realism into question. If the observer in fact takes part and influences his observation, as the observer effect suggests, then asking what the world is like without the observer is like asking what a video game, take Pac Man for example, is like without the player. Not an AI taking the place of the player, no outside entity interacting with the video game world. While we might be able to conceive of the video game world without the player, it is something we have not experienced. Even in our hypothetical version of Pac Man with no player controlling the Pac Man and no Pac Man character at all in the game, the fundamental nature of the game has changed if it is just the ghost wandering the maze in pursuit of nothing. More complex games, in fact, change the natures of their universes when observed by the player. Minecraft, for example, only simulates the actions of monsters when the player is nearby. At a certain distance the monsters cease to move, and at a greater distance they cease to exist except in certain circumstances. The world the player sees only exists in the game’s active memory when the player is nearby, and new “chunks” of the world are procedurally generated into existence when the player looks at them for the first time. One does not have to be an eccentric who believes our universe is a computer simulation, as do Elon Musk or Scott Adams, to question the certainty of the premise of realism. As intuitive as realism is, it fails to describe these video game worlds and it is possible, especially considering quantum uncertainty and the observer effect, that it fails to fully describe our world as well.

From Physics to Conspiracy Theories

Except for mathematics, science is the area of epistemology that seems most correct when measured rationally and epistemologically, which is the reason for focusing on its more subtle flaws rather than the more obvious ones in other paths of inquiry. Chemistry and classical physics have long been considered the standards of scientific rigor among the many fields, and this can be seen in how easily their predictions can be vindicated. Disciplines like climatology, which attempts to make predictions that cannot be tested until several hundred years in the future, or paleontology, which attempts to describe the past based on clues but not experimentation, have more questionable findings. We might agree that their current models of climate change or the evolution of late-Cretaceous period birds are the best evaluations of the evidence, but their findings cannot be tested in the laboratory or made into useful machines like those of chemistry or physics. This explains why such findings so easily get away from scientists and into the public forum/YouTube comments.

Outside the realms of science, we see conspiratorial thinking, sociological theories that divide the world by race, gender, class, etc. These are reason-driven but empirically untestable theories of reality applied to the “social sciences.” The only check on ethical reasoning remains emotional, and only appellate judges and law professors apply non-contradiction as a criterion to ethical truth as was prescribed by Parmenides. Even then, they apply reason to the rule of non-contradiction quite clumsily, and appellate courts can disagree quite violently on the interpretation of a statute.

The world outside scientific inquiry is obviously just as important to human thriving as the scientific, and yet it has questions that cannot be answered by experimental processes, and sometimes are fundamentally reliant on synthetic a priori judgements. They can just as easily create unfalsifiable but wild theories of the true nature of the world like those of the pre-Socratic metaphysicians. Those in certain social sciences will break down the world according to the field of study that forms their worldview. The student of African-American studies breaks down societal interaction in the struggle between the races, the student of women’s studies breaks it down into the battle of the sexes, and the student of Marxism breaks the world into classes and all historical movement into class struggle. Within each of their own frameworks, they are just as right as Plato was within his framework of forms. But they ultimately are making claims just as unfalsifiable as those who claim the world is a video game.

Conspiracy theories are a common way of doing modern politics, which came to the surface in a big way after the 2016 United States Presidential Election with each side accusing the other of conspiring to rig the election with the help of various foreign agents. Regardless of politics, about 16% of Americans believe that the Illuminati, or some other shadowy and sinister cabal, controls world events from behind the scenes, while 20% believe that extraterrestrial visitors have come to earth.18 Believers are mixed on whether those two facts are related. Conspiracy theorists cannot be dismissed as a quirk of American politics, as they affect the way people all over the world think about their perceived enemies. In the Middle East & North Africa, for example, 65% of those surveyed by the Anti-Defamation League said they agreed that “Jews are responsible for most of the world’s wars.”19 The People’s Republic of China accused the United States of secretly releasing the 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. Conspiracy theories, ranging from wacky but harmless to anti-Semitic and dangerous, are all rationally justified in the minds of those who believe them by two simple synthetic a priori assumptions: that “they” are responsible for most of the world’s problems, and “they” control empirical information. Accepting these two assumptions means that any pieces of data can be made to fit the conspiracy theory, even data that directly contradicts it. Data that contradicts the conspiracy theory may even be proof of the conspiracy in the minds of those who believe it, as it shows the power of the conspiracy to manipulate empirical information. Because believers automatically formulate their theories this way, conspiracy theories are untestable. They may be strange epistemological phenomena, but in a way, conspiracy theories are the popular equivalent of the various untestable theories put forward by metaphysicians or social scientists.

Is Experience Still Uncertain?

We know better than ever the flaws of our sensory perception, that nothing possesses a color except our minds make it appear so. We have measured the wavelengths and wave peak heights across the electromagnetic spectrum and can evaluate why certain wavelengths reflect off a certain surface while others are absorbed, but that brings the true world even further from our minds. In some sense we know how our minds interact with the world better than ever before, but we know more than ever the many points at which reality is disconnected with our perception of reality and our perception is disconnected with our interpretation of reality, as light travels from one source, bounces off a series of other objects, is focused from a limited perspective, is processed by the retina, is interpreted unconsciously by the occipital lobe, and is finally interpreted by our reason with all the individual, cultural, and linguistic biases our mental framework imports to our judgement. The “discovery” of dark matter and the size of the universe and the various fields and their corresponding spectrums of frequencies that inhabit the universe show just how limited our perspective is and how limited, therefore, our empirical data-gathering ability is.

Everyday Pragmatism and Pragmatic Philosophy

Living with this level of uncertainty would seemingly make everyday life impractical and complex technologies impossible. Skeptical humans would all be doomed to live like Pyrrho, the Greek philosopher who was allegedly so skeptical his friends and students had to keep him from walking in the middle of the road because he could not be certain of the danger of the oncoming horses and wagons.20 Everyday people, including most off-the-clock philosophers and scientists, live their life by a radically different epistemological system of pragmatism.

Charles Sanders Peirce, the American pioneer of philosophical pragmatism, said that the maxim of pragmatic thought was to “consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.”21 More simply, we can judge an idea based on how useful it is. But it was not until the late nineteenth century that he and other American philosophers began to formulate it as a theory of epistemology. Before that, it was just the part of the ordinary everyday thinking that everyone lives their lives by. In its everyday usage, pragmatism combines with habit to prevent people getting stuck in wells of uncertainty every time they walk out the front door. Pragmatism has the advantage of justifying ideas like mathematics without justifying them to some deep inherent a priori spring of wisdom or metaphysical speculation about the existence of math as an entity of its own. Pragmatism simply needs to say that we know that 7 + 5 =12 because every time we do accounting or computer science on that basis we are not left with missing cash or a computer bug.

The leading problem with the pragmatic maxim as a theory of truth is its subjectivism, or that different people sometimes have different ideas of what constitutes “practical bearings.” A philosopher sitting back and weighing what gives him or her value provides judgements that are completely subjective to that person. Even if there does happen to be an idea that has universal pragmatic value, the philosopher who focuses on himself or tries to assert that such an idea has value if that value can be rationally justified will be stuck with the uncertainty or tendency toward error as an other use of reason. Pragmatism alone cannot discover truth, though its ability to test value is very useful in science.

Is Science Pragmatism?

The epistemology of modern science derives much of its power to establish concepts with any level of certainty to the pragmatism inherent in its practice. A defense of science will generally point to those of its successes that have born the most fruit, i.e. those that make technology possible. James Clerk Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism is vindicated less by experimental results and more by the pragmatic value we get when our cell phones continue to work. It is in these areas of science where things receive the most pragmatic testing after being applied by engineers; such as chemistry, electromagnetism, optics, and Newtonian physics, that we can be assured of the merits of the existing understanding by the pragmatic value they give in our everyday lives. But science itself is not pure pragmatism, and the scientific processes of performing experiments and formulating hypotheses often leaves pragmatic value behind.

Philosopher of science Ronald Giere observed that “the realism of scientists may be thought of as a more sophisticated version of common-sense realism.”22 If this is the case, then science can be subject to the shortcomings of common-sense realism identified anciently by Melissus and Parmenides. While those aspects of science that are tested pragmatically can be corrected easily, the largely theoretical side of science is reliant on its own members to identify and propose alternatives to contradictions and shortcomings of theoretical frameworks.

Giere pointed out that in the modern era of physics, “more scientific knowledge now being produced is the product of distributed cognitive systems.”23 While each physicist might understand the overall picture of the theoretical understanding of their field, each precise subject requires dedicated experts who work particularly in that field. This may increase the total amount of expertise in the picture therefore increasing the problem-solving ability of physicists as a whole, but it also means that contradictions in scientific knowledge are more difficult to recognize because contradictory theories or data may be distributed across multiple people.

In the field of computer integrated circuit design, Moore’s Law famously predicts a doubling of the number of transistors per circuit every two years. In 1965 Gordon Moore, an engineer at Intel, made a prediction based on the first five years of integrated circuit fabrication which turned out to be far truer than he expected, which still holds true after fifty-five years. It has turned out to be far more successful than the many scientific predictions that the growth would stop based on the application of some restraint of engineering or physics, including a few by Moore himself.24 Yet Moore’s Law is usually considered to not be scientific, as it is just a prediction of the future based on pragmatic observation. The ability of scientists and scientific methods to predict the future have been thwarted on many other indications, such as theories of Malthusianism which predict worldwide overpopulation and starving on a regular basis.25 Pure reason would assume in the cases of both Malthusianism and the failure of Moore’s law a simple scenario of exponential growth reaching its inevitable end. The unpredictable aspects of the outside world and the countless factors that reason might fail to account for lead to these “reasonable” predictions failing miserably.

Scientific paradigms, particularly those that have no or only narrow practical use to everyday lives or predict the future without identifying a trend in the past are rationalized via reason and experiment. The scientific processes and systems of theory are among the most rigorous applications of reason and the most pragmatic field of inquiry we know of, but science remains limited in its certainty by the shortcomings and errors of reason.

A New Pragmatic Approach

Traditional Pragmatism gives philosophers the task of judging propositions based on their practical, useful value, but it does not provide a useful criteria for evaluating value or for creating propositions of pragmatic value that apply universally to people as a whole. The traditional pragmatism formulated by James, Dewey, and Peirce is a top-down prescriptive approach, in which the philosopher determines what ideas and methods have pragmatic (probably utilitarian) value for society as a whole, with the expectation or hope that his or her students, readers, and maybe even elected officials will implement his or her prescriptions for society.

In the interest of creating a formulation of pragmatism that takes into account the differences in values across individuals and groups, does not put undue emphasis on the values of any one person or group when evaluating, and allocates resources according to values, we need a theory of pragmatism which distributes judgements freely among individuals. This is where the Theory of Anarchic Pragmatism can help. This formulation is descriptive rather than prescriptive. It describes how individuals unconsciously make pragmatic decisions and those decisions advance ideas that further their own values. This way of looking at pragmatism is useful in evaluating theories of art, potential future technology, and the productiveness of methods of production and commerce.

The Process of Anarchic Pragmatism

The study of economic activity has discovered an unusual phenomenon: that without a rational planning body the distributed members of the economy structure their resources, labor, and consumption efficiently. A certain number of barrels of oil are produced by and for the economy without any person or decision making body to decide how much oil is needed, who will use it, who will produce it, or how it will be produced. There is a natural process by which individuals make those decisions based on balancing their wants, needs, and abilities with prices. Economists from Zhuang Zhou in the fourth century BC to Adam Smith in the eighteenth century to Ludwig von Mises in the twentieth century have described a process that has been dubbed “spontaneous order” or “extended order” by Nobel Prize winner F. A. Hayek.26 It is a kind of self-implementing natural epistemology by which each member of society can determine the costs and benefits of what they might consume or supply and can act accordingly. This process could be described as “anarchic” in that it is not managed by top-down authority while at the same time it is orderly because it is naturally coordinated by economic forces. The effect of this process on economics has been well documented by economists, but its value to epistemology has been mostly overlooked.

Technology, art, and commerce have a natural way of forwarding those things which best give people value in the same way “spontaneous order” forwards the economic practices which are most efficient. In the domains of technology, art, and commerce people make countless decisions every day, decisions that are made on a pragmatic basis. The aggregate of these decisions promotes the ideas people value most without reason having to make a generalized decision. This anarchic pragmatism works over the long run, as the aggregate of choices. It is a bottom up process, where the consequences of countless individual determinations of value are aggregated through the economic process and result in more of what individuals value. It is not anarchic in the sense that it fosters or prefers chaos, instead it is anarchic in the libertarian sense that it is a process driven by free individual choices with no need for top-down control. In some sense, it selects for the most valued ideas in the way that the process of evolutionary natural selection selects for the species most fit for survival. It is important to make the distinction that an election is not anarchic pragmatic, because an election is a mechanism whereby people force their values on others whereas archaic pragmatic interactions are voluntary and therefore in agreement with the values of all those who participate in any given interaction.

Anarchic pragmatism is a naturally occurring process which takes place as people become freer to think, speak, innovate, and conduct their own business. This mechanism can go a long way toward explaining the growth in human prosperity in the modern era, possibly further than the seventeenth century realignment of scientific epistemology. The death of the feudal and guild based societies freed up the ability of the individual to make their own economic decisions, and economic decisions distributed across a population in which each person receives the benefits or harms of the ideas that their values determine acted as a pragmatic filter on the economic activities of society.

The Anarchic Pragmatic Relationship Between Arts and Values

We can illustrate the process of anarchic pragmatism by looking at its role in art. Taste in art is largely dependent on the individual and their cultural context, but there seems is something more to it than just eight billion random and arbitrary sets of opinions. While people might be split on their preferred flavor of ice cream, ninety-nine percent of people prefer the flavor of ice cream to that of burnt spinach. But would we say that the flavor of ice cream is in some sense “objectively better” than that of spinach as a universal rule? But what if there are aliens or terrestrial animals who tend to reject the sweet in favor of the bitter, or even a small percentage of humans with very abnormal tastes? Do we say that the flavor of ice cream is better for most humans as a universal? That would be making a universal simultaneously subjective, which contradicts the meaning of a universal.

The anarchic pragmatist can say something more useful and technical: humans tend to find more value in the flavor of ice cream than in that of burnt spinach. This is not a universal, but it does accurately describe human aesthetics regarding flavor. From there, we can speculate on why they find more value in one flavor than the other, and experimental, scientific, and rational insights can help us deduce that humans like ice cream because it is sweet, and hate burnt spinach because it is bitter.

Given this insight into the aesthetics of food we can build ideas that might give new options to the aesthetic possibilities we might enjoy. We might say that it should then be the case that humans like rotting fruit, because its sweet, and hate a charred steak, because it is bitter. When such prediction fails, we might backtrack and see that human taste is more complicated than simply liking sweetness and hating bitterness. This is the role of the philosopher or theoretician (in this case, a chef) in anarchic pragmatism: to attempt to describe what about a certain idea (in this case, a recipe) causes it to give value to those who participate in it (in this case, the diners). The more accurately we can describe what about an idea gives it value, the greater our ability to create better ideas and test them out to evaluate their value. The anarchic pragmatist critic can identify new ideas and help others recognize that they might find value in them. Pixar’s 2007 animated film Ratatouille explored the role of artist and critic in a similar aesthetic model with surprising insight:

The bitter truth we critics must face is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so. But there are times when a critic truly risks something, and that is in the discovery and defense of the new. The world is often unkind to new talent, new creations. The new needs friends.27

The focus of a theoretician here is not to destroy the old and criticize others for accepting it, but to instead decipher what qualities give the old ideas value to others and help to foster those best qualities in the new. They may also help to convince others that they might find greater aesthetic value by broadening their artistic outlook. Other artistic mediums and forms have even more complicated aesthetics, and they often are interrelated with the rest of culture in a way that changes whenever anyone tries to use the same aesthetic principles to repeat an artistic success.

If art is to be judged by its effectiveness in making human beings feel profound emotions, then asking whether humans feel an ongoing compulsion to study, re-experience, and understand a piece of art, i.e. whether they find value in that art, is a much better evaluation than any critic or student of formal aesthetics could make. Whether a piece of art endures is the expression of its pragmatic value, not whether it makes a lot of money. We can say that time has judged movies like The Wizard of Oz, Star Wars, or The Shawshank Redemption to be great works of art, but not necessarily a quickly forgotten summer blockbuster.

Technology Vindicated by Anarchic Pragmatism

Those who pass judgement on modernism almost always do so on the basis of whether or not they see value in technology. Even those who are dismissive of science often show through their actions that the theory of electromagnetism has pragmatic value to them whenever they look at their cell phone. Technology has a relationship to science, but it would not accurately describe the process or do justice to the countless engineers and innovators of technology to call science and technology synonymous. Technology is uniquely pragmatic, as the criterion for successful technology is not whether it is true or not true but whether it works and is valuable or does not work or is not valuable. Technology does not just benefit from the body of scientific theories, it tests them far more extensively than any scientist could ever hope to, and it shows that the theory is not just the consequence of the potentially flawed framework of reasoning of the scientist. The relationship between the scientific study of anatomy, physiology, and chemistry with their technological applications in medicine shows the process in action.

Craft and technology demonstrate how the insights of those who study the pragmatically successful works of others can be used to build up the pragmatic knowledge that makes greater and greater value possible. The architect does not reason out a structure from scratch, he rather sees the forms and techniques that have provided value for thousands of years and predicts what synthesis of these will produce value for the contemporary and future users of the structure. He has seen an arch in hundreds of structures and designs a slight variation on it that he believes will produce value aesthetically and structurally in his current design.

We can see how the process of anarchic pragmatism has created leaps in medicine for years, while the strange leap in pricing might be explained by individual choice being removed from medical pricing. Pharmaceuticals and medical procedures undergo several levels of pragmatic testing, the last of which is anarchic pragmatic. Clinical trials test for maximum improvement to the patient while hoping for minimal side effects, the two values all patients look for in a medicine. This round of testing uses simple pragmatism as an epistemological guide. The final round of testing for a medicine is when it is introduced to the market, and patients and doctors chose whether or not to use the treatments. This round of testing is anarchic pragmatic. Insofar as people pay for their own healthcare, medicine is also tested for efficiency, but throughout the western world the price of medicine is rarely a factor in customer choice because of health insurance plans and state-funded healthcare. This can help explain why prices of healthcare have risen rapidly in the United States over the past several decades, especially when innovations like those in electronics become more affordable every year. Because the system does not allow for an anarchic pragmatist judgement of the value of affordability in medicine, affordability is not subject to the innovations other aspects of medicine are.

When people choose over time which technology they will use and buy, it shows what technology has value based on a broader array of human values than any single person can consider. Surprising ideas can sometimes have huge value to people, such as Steve Jobs’s insight that aesthetics and user experience are more valuable to many home computer users than raw computing power. Only in a system in which individuals can express those values through their purchases could such a counterintuitive idea prevail. When people choose over time which technology they will use and buy, it shows what technology has value based on a broader array of human values than any single person can consider.

Practicality, Expertise, and the Economy

Why do centrally planned economies tend to fail where “chaotic” free markets tend to succeed? After all, a centrally planned economy brings to bear the best experts and the best knowledge and reasoning to coordinate every economic decision, whereas in a free market each consumer and firm makes a decision of their own, usually without coordination or nearly as much technical analysis as a Soviet ministry of industry could bring into the decision. If it were possible to add up the gross amount of reason that goes into a centrally planned economic decision versus a free market individual or firm’s economic decision, the free market agent would have only a tiny fraction of the central planning agency’s amount of reason. This suggests that economic decisions succeed not because of the total amount of reason contributed to the decision, but because some kind of natural mechanism selects for the success of those decisions and the actors who make them. This mechanism is the anarchic pragmatist process. It means that better ideas and the businesses that uses them do better economically while those which use inferior methods may fail. It balances quality and prices according to the values of the customer.

The failure of the centrally planned economies and relative successes of relatively free-market economies illustrates the superiority of the anarchic pragmatic process over that of relying on expert reason in making everyday economic decisions. The potential problems of making commercial decisions based on top-down expert reason was unintentionally illustrated in 1998 by another Nobel Prize-winning economist, Paul Krugman, with his now infamous prediction about the impact of the internet on the economy:

The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in ‘Metcalfe’s law’–which states that the number of potential connections in a network is proportional to the square of the number of participants–becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.28

The transformation of the economy of 1990 into the “information age” economy of 2020 was not a choice made by any expert or institutional body, nor was it implemented in a pre-planned and coordinated way. It happened through anarchic pragmatism, as people and newly founded firms discovered new commercial uses for emerging technologies and tested whether people and businesses found them to be valuable. A lot of their ideas turned out not to be as useful to businesses or enjoyable to consumers as their inventors thought they would be, and the economic history of the late ’90s and early ’00s is littered with the corpses of failed tech firms and worthless internet products. But the ideas that did survive are now foundational to the way modern people work, consume art, buy, and learn.

People deciding what to buy decides how labor and resources are allocated more efficiently than reason alone can decide. In a competitive market, firms must figure out how satisfy the public’s values as inexpensively, ergo efficiently, as possible. To survive long-term, they must continue to produce value on a long-term basis. Unsustainable business practices that do not produce long-term value are rejected like the number one radio hits of last summer. It is the anarchic pragmatic process of people freely trying to maximize their economic value that selects for the best economic and commercial practices.

The distributed nature of these determinations means that each participant in the process must be free to choose what art, technology, or economic activity creates pragmatic value for each individual in order for the anarchic pragmatic process to occur. Anarchic pragmatism and the anarchic pragmatist have a relationship like that of economics and the economist. Anarchic pragmatism can refer to the natural process by which the public’s prioritized values act as a pragmatic decision-making mechanism, or it can refer the study and attempts to describe that process. Economics, like anarchic pragmatism, is a decentralized process that happens naturally as a consequence of human actions, and partially functions as the medium through which anarchic pragmatist decisions have real-world consequences.

Anarchic pragmatism can take into account more than just reason alone, but also deep underlying psychological factors, cultural standards, and everyday practicality. As an epistemology, it allows for the diversity of human beliefs, cultures, and perspectives without conceding the relativity of truth, because it does not claim to address the problem of truth.

The Boundaries of Anarchic Pragmatism

Anarchic pragmatism is a system of epistemology, but it is one that occurs naturally and implements itself as it discovers which ideas have value. It does not discover truth directly, and we can only call its discoveries truth insofar as we believe value is an indicator of truth. The “anarchic pragmatist” does not have to believe that the crowd is always right, only that they find value in what they have chosen. An anarchic pragmatist may believe that others find value in sin or frivolity or that others might find more value by agreeing with him or her. He or she has a duty to convince others to search for value in better places just as a film critic has a duty to try to convince readers that there is greater value to be found in certain films.

Questions that are not or cannot be made subject to this process of individual choices selecting for ideas to maximize value cannot be addressed by anarchic pragmatism. The answers to the big questions of metaphysics and the origin of man and the universe are left to speculators to continue to chase in circles for the rest of human history. The only ethics this system of thought can give us is this: we should act in a way that permits the anarchic pragmatic process to happen as much as possible, because it will continue to increase our overall value. The only synthetic a priori assumption we have to import into such a determination is that we should maximize value. From this one assumption, we can extrapolate to other virtues. For example, we should reject murder because it destroys a great amount of human value, meaning the value each person has for themselves and that others may have for them as well. We should allow people to choose what products and art they wish to consume, and to believe what they wish, and to try radical new ideas, because this freedom is necessary for the anarchic pragmatic process to continue to maximize human value.

A weakness of anarchic pragmatism can be in accepting ideas as valuable even when their underlying logic is questionable or outright incoherent. For example, many people find value in various forms of alternative medicine, and while it would be ludicrous to say that all alternative medicine is bunk and works only through a placebo effect, any student of science or medicine can look at the justifications given by the sellers and advocates of these medicines and see that they obviously lack the most basic understanding of the fields that they address. But if people find value in such poorly justified, even irrational, ideas, on what grounds can the anarchic pragmatist reject them? We must therefore acknowledge that not every free decision is rational, nor does every free decision succeed in maximizing value for the person making it. Sometimes, millions of people get a decision wrong. But there is a limit on how wrong they can be. Someone can waste money on a harmless placebo many times, but only once on a poison pill. We can safely assume that how quickly ideas that produce noticeable negative value and are therefore rejected is proportional to just how negative that value is. Over an extended period, then, we may see a slow decline in alternative medicine, or perhaps more effective, dietary driven, reasonable alternative practices gain prominence. Counterproductive decisions can be corrected through the process of anarchic pragmatism when diluted in a large population and given time to filter out.

Reason provides us with ideas that can lead to an increase of pragmatic value, even if it cannot give us certain knowledge of the truth of those ideas. This strongly indicates that reason does, in fact, have pragmatic value. If pragmatic value has some correlation with truth, then we do not have to say “Farewell to Reason,” as Feyerabend claimed. We can find its connection to value and knowledge through anarchic pragmatism.

The Responsibilities of the Anarchic Pragmatist

The role of an anarchic pragmatist philosopher or a theoretician in art, technology, and commerce is not to decide what is true or false or even to decide what has value. It is rather to attempt to evaluate, through reason, empiricism, and emotion, why something has created value for people in a way that allows others to produce their own art/technology/products to be tested in the world. A good aesthetic critic helps others find more value in a work of art. Correctly predicting what ideas will be found useful by the process of anarchic pragmatism is like a scientific theory that has been found to have predictive power.

The difference between anarchic pragmatism and traditional Piece/Dewey/James pragmatism is that traditional pragmatism involves a philosopher determining what has pragmatic value and applying his conclusion broadly. Anarchic pragmatism only allows the philosopher to attempt to predict what will have value. The actual determination of value is made by each individual. Those who would try to improve society as a whole would do best to try to maximize and improve the range of ideas that can be tested while strengthening each individual’s ability to choose between those ideas, and then allowing those ideas judged as valuable by society to gain in institutional prominence, those ideas judged as valuable by only a few to exist in so far as those few are willing to support them, and to allow those ideas that are judged to have no value or to have lost the value they once had to wither and die from lack of support.

An individual trying to decide how he or she ought to live his life through the lens of Anarchic Pragmatism should evaluate his or her own values and then compare them to how others who share those values live their lives and how successful that lifestyle is in fulfilling those values. Anarchic pragmatism could apply to fields other than commerce, technology, and art, but cannot and should not be applied to any epistemological endeavor which seeks pure truth. Anarchic pragmatism can, however, test how our values affect what each of us as an individual gets out of life.

Written June 2020

Endnotes:

- G. S Kirk, J. E. Raven, and M. Schofield, The Presocratic Philosophers (Cambridge University Press, 2007), 270. ↩︎

- Ibid., 94. ↩︎

- Chris Mortensen, “Change and Inconsistency,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Spring 2020 Edition), section 3. ↩︎

- Plato, The Republic, trans. Benjamin Jowett (Oxford, 1888), 215. ↩︎

- Quoted from Kenneth Einar Himma, “Anselm: Ontological Argument for God’s Existence,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (University of Tennessee at Martin, 1995-2020), section 3. ↩︎

- Bertrand Russell, Autobiography (1967-1969, repr. New York: Routledge, 1978), 60. ↩︎

- Graham Oppy, “Ancient Skepticism,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Spring 2020 Edition), introduction. ↩︎

- G. S Kirk, J. E. Raven, and M. Schofield, The Presocratic Philosophers (Cambridge University Press, 2007), 399. ↩︎

- Ibid., 247. ↩︎

- Anthony Kenny, A New History of Western Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 2010), 122. ↩︎

- Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason, trans. J. M. D. Meiklejohn (1781, repr. Project Gutenberg, 2003), introduction section VI. ↩︎

- Ibid., introduction section V. ↩︎

- Paul Feyerabend, Farewell to Reason (New York: Verso, 1987), 297. ↩︎

- Brian Greene, The Hidden Reality: Parallel Universes and the Deep Laws of the Cosmos (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), 11, 272, 314, 217. ↩︎

- Lee Smolin, The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory and What Comes Next (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006), 12. Note that Smolin is not inclined to believe that the scientific method is fundamentally flawed, he rather is railing about the institutional and peer-supported orthodoxy of the dominance of string theories in the world of modern physics, despite the lack of a clear string theory hypothesis or a way that string theory might be falsified. But the fact that the scientific consensus can be so swayed by institutional shortcomings and peer pressure can also suggest that the scientific consensus is far from perfectly rigorous. ↩︎

- Ibid., 14. ↩︎

- Weizmann Institute of Science, “Quantum Theory Demonstrated: Observation Affects Reality,” ScienceDaily (ScienceDaily, 27 February 1998). ↩︎

- Angela Wang, “America is a nation of conspiracy theorists. Here are the most commonly believed in phenomena,” Insider (Insider Inc., 18 July 2019). ↩︎

- Anti-Defamation League, “ADL Global 100,” (Anti -Defamation League, 2019). ↩︎

- Katja Vogt, “Ancient Skepticism,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Fall 2018 Edition), section 4.2. ↩︎

- Charles S. Peirce, “How to Make Our Ideas Clear,” Popular Science Monthly 12 (January 1878): 286-302. ↩︎

- Ronald N. Giere, Scientific Perspectivism (University of Chicago Press, 2006), 4. ↩︎

- Ibid., 116. ↩︎

- Gordon Moore, “Excerpts from A Conversation with Gordon Moore: Moore’s Law,” (Video Transcript, Intel, 2006). ↩︎

- For the best-known twentieth century Malthusian prediction, see Paul R. Erlich, The Population Bomb (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1968). Erlich predicted an apocalyptic worldwide famine in the 1970s or 1980s, but failed to take into account several important factors, such as the potential for non-linear resource growth and cultural factors affecting the birthrate, as was pointed out in Julian L. Simon and Herman Kahn, The Resourceful Earth (New York: Basil Blackwell Inc., 1984). ↩︎

- F.A. Hayek, The Fatal Conceit (University of Chicago Press, 1988). ↩︎

- Ratatouille, dir. Brad Bird, (Buena Vista, CA: Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, 2007). Ratatouille’s focus on food as an artistic medium is the ideal choice for this kind of exploration of aesthetics because it is the artistic medium that is most obviously focused on human experience and values. Food itself has very little room for metanarratives, postmodernism, deconstructionist criticism, or other theories that devalue or convolute the importance of the individual experience in evaluating art. ↩︎

- Jay Yarow, “Paul Krugman Responds To All The People Throwing Around His Old Internet Quote,” Business Insider (Insider Inc., 30 December 2013). Dr. Krugman claimed in 2013 that his quote was taken out of context from a 1998 Time article, saying that “the point was to be fun and provocative, not to engage in careful forecasting.” Further examination shows that Krugman wrote for Time in 1996, but the time article does not contain that quote. It was in fact from the 10 June 1998 issue of Red Herring and was not in the context Dr. Krugman claimed in his letter in Business Insider. For more information, see David Emery, “Did Paul Krugman Say the Internet’s Effect on the World Economy Would Be ‘No Greater Than the Fax Machine’s?” Snopes (Snopes Media Group Inc., 7 June 2018). ↩︎