When the United States entered the World War in 1917, the face of comic Charlie Chaplin in character as “The Little Tramp” was possibly the most famous in the world. In the years leading up to the United States’ involvement in the Second World War, a face much like it would be known across the globe as the face of the war. Hitler and Chaplin shared the same iconic mustache, were the same age, and came from similarly impoverished circumstances. Yet they were opposed in almost every way. While Adolf Hitler spread his rhetoric while speaking at massive gatherings, Chaplin phrased his message against Hitler in the form of comic tragic film.

The Great Dictator (1940) was Chaplin’s statement to the United States attempting to dissuade its people from their reluctance to intervene against Hitler, which he attempts to do by both ridiculing and demonizing Hynkel, his proxy of Hitler. It therefore reflects Chaplin’s impression of the culture, values, and concerns of the United States, gained from the perspective of a British man who had lived most of his life in America.

Hitler had been in the news of the United States since 1933, yelling and marching but never presenting enough of a clear threat to American interests to provoke open war. Britain and France had been pursuing a policy of appeasement, allowing the 1936 Remilitarization of the Rhineland and de-facto end of the Treaty of Versailles. The United States had very little inclination toward being actively involved in European events, particularly when Britain was still on good terms with Germany.

The public face of Nazism in the United States was the “German-American Bund” (“Amerikadeutscher Volksbund”), which attempted to create the impression of a large movement of patriotic American support for Hitler’s objectives. Hitler’s government had sponsored the movement until diplomatic pressures forced Berlin to sever ties with the bund in 1935. The Bund lived on, however, and even held a Nazi-style rally in Madison Square Garden on 20 February 1939. The Bund may have actually served to increase the fear of Nazism in many Americans, though not enough so to force the United States into war.1

Actual Nazis and Nazi sympathizers were a small minority, but they were present. Chaplin spoke in his 1964 autobiography of an encounter with one: “A young New York scion asked me in a benign way why I was so anti-Nazi. I said because they were anti-people. ‘Of course,’ he said, as though making a sudden discovery, ‘you’re a Jew, aren’t you?’

“’One doesn’t have to be a Jew to be anti-Nazi,’ I answered. ‘All one has to be is a normal decent human being.’ And so the subject was dropped.”2

Chaplin had previously been referred to as a “disgusting Jewish acrobat” in Juden sehen dich an (Jews Are Looking at You), a 1934 German propaganda book. He was not actually Jewish, though both his half-brother and his wife at the time were partially of Jewish ancestry. He had opposed Hitler’s regime since it had taken power in 1933, and found the newsreels of Hitler speaking loudly and animatedly both ridiculous and terrifying. Since his earliest films in 1914, Chaplin had performed in character as “The Little Tramp,” a bumbling but good-natured vagrant in baggy clothes, big shoes, a small bowler hat, and a black toothbrush moustache just like the one Adolf Hitler would later adopt. This character had brought Chaplin worldwide fame and made him the highest paid entertainer in the world by 1916. Chaplin had been a star of the silent screen for 20 years when he released Modern Times (1936) and began looking for a new project, but his increasing concern about Hitler was affecting his creativity and he remained reluctant to make the transition from silent to sound films.3 In early 1937, a friend suggested that he could make a parody of Hitler based on mistaken identity, with Chaplin playing both Hitler and The Tramp.

To preserve his message and maintain his own artistic vision of the film, Chaplin intended to control every aspect of the production. He wrote the script, produced and directed the production, played both lead characters, and committed almost $2 million of his own money to independently finance the project. He also wrote a large portion of the film’s musical score with the assistance of Meredith Wilson, future writer of The Music Man. To play his new Hitler character, he studied newsreels of Hitler’s speeches and imitated them with comedic exaggerations.

The war had not yet begun during the 2 years Chaplin spent developing and writing the film, but Chaplin already saw Hitler as a clear enemy and that conflict with him would be inevitable. Germany invaded Poland and war was declared by England and France in September of 1939, just days before principal photography for The Great Dictator commenced. The majority of Americans, 84 percent according to a 1939 poll, supported the Allies when the war began, but most wanted America to stay out of active involvement in the war.4

At the time, the Motion Picture Production Code considered so-called “hate films” off limits and recommended “special care” in “avoiding picturizing in an unfavorable light another country’s religion, history, institutions, prominent people, and citizenry.” This, combined with the possibility of being banned in countries that still supported appeasement, necessitated the use of parody names for Hitler (who was renamed Hynkel) and the rest of the characters and nations involved.5 After 1941, Hitler became the number one target for satire, and animator Tex Avery even put a message in Blitz Wolf (1942) saying, “The Wolf in this photoplay is NOT fictitious. Any similarity between this Wolf and that (*!!*%) jerk Hitler is purely intentional!”

The Great Dictator begins during the First World War with Chaplin’s character, a Jewish Barber turned soldier, on the Western Front for the “Tomanian” army. He saves the life of Commander Shultz (played by Reginald Gardiner) a wounded pilot, and flies (upside down) with him to safety, but is wounded in the crash landing and spends the next 20 years in a military hospital.

In the meantime, the party of “Adenoid Hynkel” rises to power. At a massive rally, The “Fooey” (Führer) Hynkel shouts and rants in German sounding gibberish about the beauty of the Arians and the danger of the Jewish people. “Der Juden! Une da shuft der sauerkraut me da Juden!” Hynkel yells, snorting and growling angrily as the microphones on the stand comically bend away from his face. “Democracy schtoonk! Liberty schtoonk!” He is flanked by his advisors Garbitsch (pronounced “Garbage,” parody of Joseph Goebbels, played by Henry Daniell) and Herring (parody of Hermann Göring, played by Billy Gilbert).

The Jewish Barber leaves the military hospital, unaware of the twenty years that have passed, and returns to his barbershop in the Jewish Ghetto. He falls in love with Hannah (Paulette Goddard), who aids him in resisting Stormtroopers. Schultz, who now governs the Ghetto and remembers The Barber saving his life, intercedes on their behalf. Schultz protests to Hynkel on behalf of the Jewish people and is sent to a concentration camp along with The Jewish Barber. Hannah and her family escape to neighboring country of Osterlich.

Hynkel meets with Benzino Napaloni (parody of Benito Mussolini, played by Jack Oakie), who is the dictator of “Bacteria” (Italy) and has competing plans to invade Osterlich. Napaloni is big and loud, exclaiming “Hello-a Hynkie!” in a ridiculously exaggerated Italian accent while slapping Hynkel and knocking him out of his chair. They argue over the troops on the border of Osterlich and their argument decays into a food fight. Garbitsch persuades Hynkel to agree to a treaty with Napaloni to move troops from the border, but plans to invade immediately after.

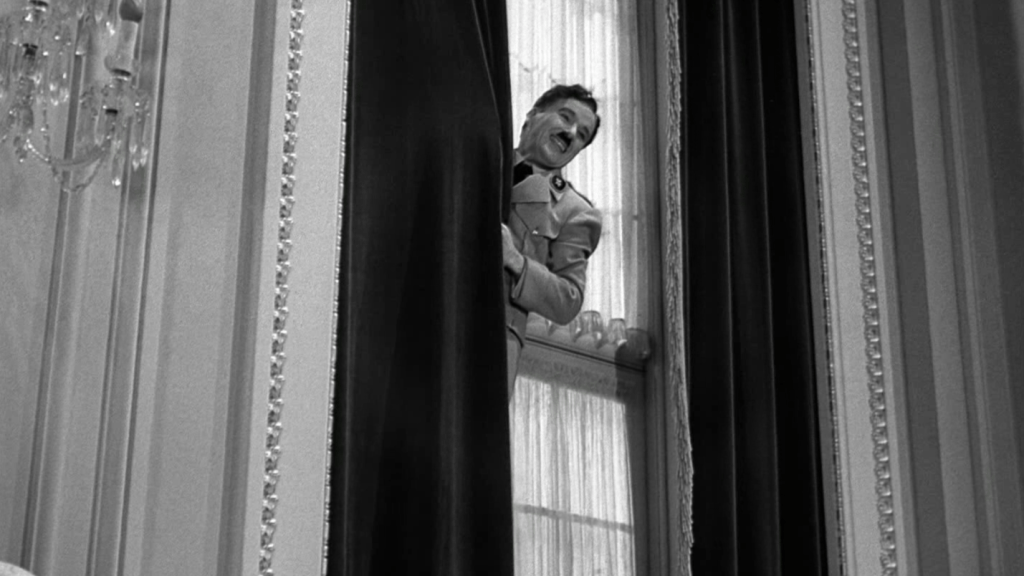

Shultz and The Barber escape from the concentration camp but encounter Tomanian troops on the border, who mistake The Barber for Hynkel and take him to a rally. After Garbitsch proclaims that “democracy, liberty, and equality are words to fool the people… therefore we thankfully abolish them,” The Barber, dressed in the uniform of Hynkel’s army, is called upon to make a speech. Chaplin ends the film by breaking character to deliver a speech to the audience pleading for peace and human brotherhood.6

The Great Dictator premiered on 15 October 1940 in New York City. Bosley Crowther, film critic for The New York Times, said about the star-studded opening night “No event in the history of the screen has ever been anticipated with more hopeful excitement than the première of this film… The prospect of little “Charlot,” the most universally loved character in all the world, directing his superlative talent for ridicule against the most dangerously evil man alive has loomed as a titanic jest, a transcendent paradox. And the happy report this morning is that it comes off magnificently.”7 The film was nominated for 5 Academy Awards: Outstanding Production, Best Actor for Chaplin, Best Supporting Actor for Oakie, Best Writing (Original Screenplay), and Best Music (Original Score) for Meredith Willson.

The film was massively successful, making over $5 million at the box office on its $2 million budget in the United States alone, and at least $6 million more overseas.8 Chaplin and Oakie were praised by critics for their portrayals of the dictators: “Whatever fate it was that decreed Adolf Hitler should look like Charlie must have ordained this opportunity, for the caricature of the former is devastating.”9

Critics were not as kind to the speech that ends the film. The same New York Times review that praised Chaplin’s performance said of the speech: “The effect is bewildering, and what should be the climax becomes flat and seemingly maudlin.”10 Other reviewers were more critical, with Newsweek calling Chaplin’s words “frighteningly bad.”11

The speech was far more popular with the public than with film critics, and Chaplin was asked to deliver it at President Roosevelt’s third Inaugural Gala on 19 January 1941. The speech is given directly into the camera to the audience, and Chaplin delivers it in his natural voice. It acts as a rhetorical summary of those things he said in the film, and contains appeals to American ideals as he saw them.

Though the period now referred to as the “Progressive Era” ended with the First World War, many of the ideals and philosophies that dominated the politics of that era had survived the crash and years of economic depression. The possibility of reaching utopia through scientific progress was an ideal still held by many socialists and capitalists in the United States. Chaplin appeals to the utilitarian progressive thought when he says “The aeroplane and the radio have brought us closer together. The very nature of these inventions cries out for the goodness in men – cries out for universal brotherhood – for the unity of us all,” and “Let us fight for a world of reason, a world where science and progress will lead to all men’s happiness.”

Appealing to progressivism is difficult in criticizing Nazi Germany, as Hitler shared many of the ideals of American progressives. Not only did Hitler implement vigorous programs working toward industrialization and scientific society, but he also was working to implement eugenics on a national level. There had been years of support for eugenics programs to racially improve the population from many American progressives, including Charles A. Lindbergh, the legendary pilot and the spokesperson for the non-interventionist America First Committee.12 Chaplin therefore declares dictators as unable and unwilling to truly achieve progressive goals: “By the promise of these things, brutes have risen to power. But they lie! They do not fulfill that promise. They never will!”

The speech also makes an appeal aimed for Americans who did not share in progressive views; those who felt disillusioned by the promises of technology or had a more reactionary view towards the changes of the past decades. “We have developed speed, but we have shut ourselves in. Machinery that gives abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical. Our cleverness, hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little. More than machinery we need humanity. More than cleverness we need kindness and gentleness.”

Chaplin also tried to ensure that his pleas for brotherhood and kindness could not be construed as pacifism: “Soldiers! Don’t fight for slavery! Fight for liberty!… Soldiers! In the name of democracy, let us unite!” He is arguing for peace through victory, and for World War One’s rhetorical objective of “Making the world safe for Democracy.”

Chaplin spends a great deal of the body of the film portraying Hynkel/Hitler and his regime as a personification of everything Americans of 1940 despise, while portraying the Jewish people as almost identical to Americans in their behavior and values. When Shultz proposes a plan to have the Jewish people assassinate Hynkel, and after a farcical attempt to cast lots for the ‘honor,’ they decide against violence. The Jews in the ghetto say repeatedly that they just want to go about their business and live in peace, which is exactly what the non-interventionists in the US wanted to do. They lament about the difficulty in finding employment, which much of the United States can sympathize with after a decade of economic depression. However, it’s made clear throughout the film that as long as men like Hynkel, Garbitsch, and Napaloni have power, peace can only be a temporary illusion.

The demonization of the regime can be seen throughout the supporting details of the film, such as when Hynkel’s motorcade passes defiled works of art including versions of the Venus de Milo and August Rodin’s The Thinker raising their arms to the “Sieg Heil” salute. The symbols of the two dictatorships in the film have been replaced for the dual purposes of eliminating direct references to the real-life regimes and for creating visual symbolism for purposes both humorous and ominous. Napaloni’s symbol is a pair of dice on a black patch, possibly a reference to the gambling and, by extension, organized crime that Americans associated with Italian immigrants during that period. It may have also been a reference to the fact that Napaloni is gambling in his dealings with Hynkel.

Hynkel’s symbol, which takes the place of the Swastika, consists of two thick black Xs forming a “double cross.” The obviously implied message to the United States was that Hitler would betray them or anyone else when it became expedient for the spread of his power, and therefore continued attempts to stay out of war will merely prolong the violence.

This message is further illustrated in the iconic scene in which Hynkel tosses, kicks, and even dances with a large inflated globe. “Aut Caesar aut nullus,” Hynkel says to the globe. “Emperor of the world! My world!” The Latin phrase loosely translates as “either emperor or nothing.” The soft strings of the prelude from the Wagner’s opera Lohengrin play as he holds the globe in his arms and squeezes until it bursts, and the dictator bursts into tears.

While Hynkel is portrayed humorously it’s quite clear that there’s nothing funny about his intentions or the injustices he commits. The only thing remotely funny about Garbitsch is his name, which makes it abundantly clear what he produces and feeds to the minds of the people in his position as Minister in Propaganda. His is the voice of cold menace in Hynkel’s regime, as he hints “I thought your reference to the Jews might have been a little more violent” after a Hynkel rally.

Herring, on the other hand, is full of gags, mostly based on his weight. The Great Dictator was part of a tradition that lasted throughout the war of jokes making of fun of Göring’s perceived worshipful attitude toward Hitler, his exaggerated habit of wearing a lot of metals, and his girth, all of which can been seen five years later in the animated Bugs Bunny short Herr Meets Hare (Warner Brothers Animation, 1945). Herring is also seen presenting Hynkel with various worthless war-related gadgets, like an ineffective bullet proof vest or a parachute hat. Though the film is more dismissive of the threat of Nazi technology than the American public, it has one veiled warning, when Herring exclaims to Hynkel with glee: “We’ve just discovered the most wonderful, the most marvelous poison gas. It will kill everybody!”

That threat was likely intended by Chaplin as a warning to America about Hitler’s willingness to kill everybody for as long as he could get away with it. Neither he, nor the American public, were yet aware of the full extent of the holocaust or the use of Zyklon B for human extermination, and Chaplin later said “Had I known the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made “The Great Dictator;” I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis.”13

At the time of the release, many reviewers in the United States already held Chaplin’s future view about making fun of the “homicidal insanity of the Nazis.” Many journalists criticized what could be seen as the trivialization of horrible acts, and Time asserted that Hitler was himself too sinister for comedy.14 These sentiments, however, did not appear to be shared by most audiences or even other filmmakers. The ridicule of dictators was big business for a brief period during the war, and The Three Stooges’ I’ll Never Heil Again (1941) even advertised on its theatrical poster, “Hilarious howls with Hollywood’s Daffy Dictators.”

These films persisted throughout the war, even as casualties mounted and the brutality of the dictators was slowly revealed to the world, and were especially common in animation. There were at least 10 theatrical animated shorts produced between Warner Brothers, MGM, and Disney featuring a comical Hitler, the most notable of which was Oscar winner Der Fuehrer’s Face (Walt Disney Productions, 1943). Before the war, animators had made the openly pacifist films such as Ferdinand the Bull (Walt Disney Productions, 1938) and Peace on Earth (MGM, 1939).

Disney was a member of The America First Committee, the largest and most vocal anti-war movement in 1940 and 1941. The movement also included the Kennedys, Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, Frank Lloyd Wright, many business leaders, and future president Gerald Ford. Most of these individuals were looking to avoid getting entangled in the bloodshed like that of the last war, which they believed the US was fooled into with exaggerated stories of German atrocities in Belgium. A few, however, followed anti-Semitic conspiracy theories like those that fueled the Nazi propaganda machine. Henry Ford and Kennedy Sr. were among the latter.

In the 1920s, legendary industrialist Henry Ford had published anti-Semitic articles and conspiracy theories about greedy Jewish financers starting the First World War in his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, and a book series, The International Jew. The German editions were popular with future Nazi leaders, and Hitler allegedly told a Detroit News reporter in 1931, “I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration.”15 By the 1930s, Ford had toned down his rhetoric, and was using alternative phrases like “greedy financiers” in his anti-war conspiracy theories.

Shortly after the release of The Great Dictator in October of 1940, Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. resigned under pressure from Roosevelt as Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Outspoken about British involvement in an alleged Jewish conspiracy to profit from war, he told a group of Hollywood executives they would be “responsible for pushing the United States into war against the Nazis unless you stop your anti-Nazi films, your anti-Hitler propaganda, your anti-German propaganda. When war breaks out, the American people are going to turn on American Jewry.”16

These were not the people that Chaplin was hoping to convince; rather they were those that Chaplin knew his message would be competing with. Throughout the film, with both comedy and tragedy, he states a message targeted to everything he believes about the collective heart and mind the world in general, and America in particular. The attack at Pearl Harbor changed everything for the United States, but it was the last in a long road of events leading to the war. Among the many landmarks on that road to war, The Great Dictator remains one of the most striking and the most revealing of the American character.

Written November 2016

Endnotes:

- Joachim Remak, “”Friends of The New Germany”: The Bund and German American Relations.” The Journal of Modern History (1957): 38-41. ↩︎

- Charlie Chaplin, My Autobiography (New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1964). ↩︎

- Chaplin, My Autobiography. ↩︎

- James A. Henretta, et al., America: A Concise History (Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2015). ↩︎

- David Welky, The Moguls and the Dictators: Hollywood and the Coming of World War II (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008). ↩︎

- The Great Dictator, Dir. Charles Chaplin (1940). ↩︎

- Bosley Crowther, “The Screen in Review; ‘The Great Dictator,’ by and With Charlie Chaplin, Tragi-Comic Fable of the Unhappy Lot of Decent Folk in a Totalitarian Land,” The New York Times (16 October 1940). ↩︎

- Box office/business for The Great Dictator. n.d. (IMDB), http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0032553/business. ↩︎

- Crowther, The Screen in Review. ↩︎

- Crowther, The Screen in Review. ↩︎

- John O’Hara, “Charlie, Charley,” Newsweek (28 October 1940). ↩︎

- Max Wallace, The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich (New York City: St. Martin’s Press, 2004). ↩︎

- Chaplin, My Autobiography. ↩︎

- Robert Cole, “Anglo-American Anti-fascist Film Propaganda in a Time of Neutrality: The Great Dictator, 1940.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television (2001): 137-152. ↩︎

- Max Wallace, The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich (New York City: St. Martin’s Press, 2004). ↩︎

- David Nasaw, The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy (London: Penguin Group, 2012). ↩︎