Spoiler alert!

Snape kills Dumbledore.

Tyler Durden is The Narrator.

Darth Vader is Luke’s father.

Krisin shot JR.

Iron Man Dies (like anyone cares).

Game of Thrones goes nowhere and everybody dies.

Mrs. Bates was Norman in a wig.

Rosebud is Mr. Kane’s sled.

and the dish ran away with the spoon.

Now before you all start sending me emails that remind me why I don’t have a comments section, let me spoil one more thing for you: spoilers are a good thing. Some people go to a lot of effort to avoid them, and avoid talking about key parts of media to avoid the possibility of spoilers. It’s not worth the effort.

Outside the mystery genre, “spoilers” don’t spoil anything, and we’re damaging our enjoyment of movies, books, and TV by being so careful about them. As critic James Poniewozik said, “Any story that can be ruined by giving away the ending wasn’t worth your time in the first place.”1

Take the Star Wars example: Is The Empire Strikes Back spoiled by knowing Darth Vader is Luke’s father? Probably not. Not for me anyway, I’ve watched the original Star Wars Trilogy since before I can remember. I watch it for better or worse, in sickness and health. Because I watch it if I’m sick there’s a not unreasonable chance Star Wars will be the last thing I see. Is it spoiled because I know almost everything about it? No, I love it more every time. Knowing Darth Vader is Luke’s father was never spoiled for me, I knew it before I even knew what the word father meant.

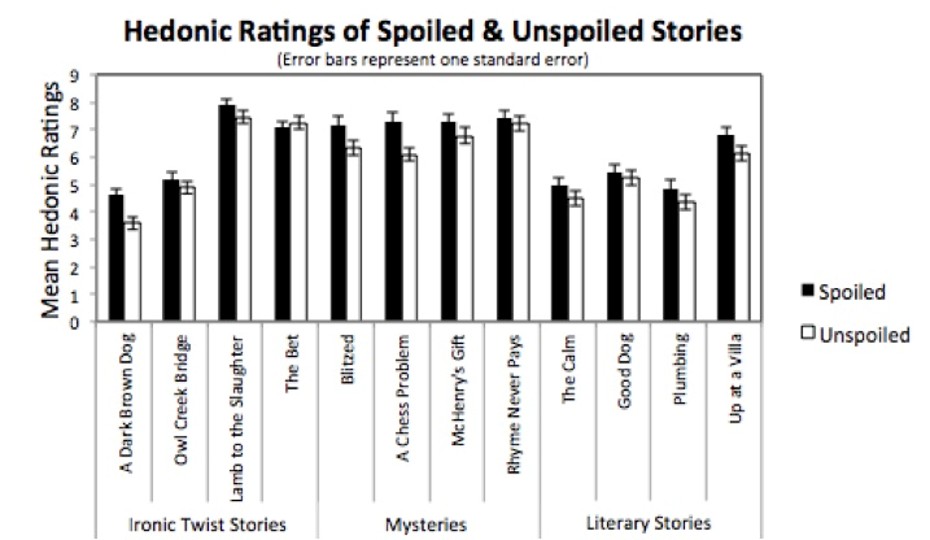

This graph is of an experiment done by a Dr. Christenfeld at the University of California San Diego. He took 12 stories across 3 genres, and had two groups read the stories, half of them had them spoiled, half didn’t. And afterword the group that had the story spoiled reported a consistently higher level of enjoyment across the nine stories told.2 Worrying about spoilers stifles discussion of movies, it makes movies, and the audience, focus on big reveals and which old character will die instead of focusing on storytelling.

Historically, no one really cared about spoilers outside mystery stories, and many authors went out of their way to tell you what will happen before it does. Some of the best ones still do. The full title of the play ‘The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark,’ should give you a clue as to what happens in the end.

Modern anti-spoiler marketing originated with Alfred Hitchcock’s idea in 1960 to market Psycho with an anti-spoiler campaign. But Hitchcock, the Master of Suspense, didn’t actually care about spoilers and found suspense more effective when the audience knows what’s going to happen, but is hoping that somehow it won’t. And we do this, even in movies we’ve already seen, we’re quietly willing things to go right. Suspense is not surprise. This is Hitchcock’s example:

If you’re watching a scene, maybe a group of friends or family having a conversation around a table, and suddenly, unexpectedly, a bomb under the table goes off, killing a bunch of the characters, that’s a surprise, only interesting in some kind of absurdist way.3

If you have the same scene, but it’s spoiled for you that there’s a bomb under the table and it will go off and kill a bunch of the characters in 15 minutes, that’s where suspense becomes a factor. We sit there willing someone to look under the table, their conversation suddenly has an ironic edge, it gives meaning to what otherwise wouldn’t hold nearly as much interest.

Hitchcock asked audiences not to spoil the ending of Psycho as a marketing gimmick, not because the movie relies on it. He new better than anyone that storytelling is not about what happens, it’s about how it happens.

This is the better way to understand media. Years ago, I read The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky. It was a big book, about 800 dense pages, and it was difficult to keep track of the characters with their Russian names and multiple nicknames. Looking that stuff up naturally involved running into some spoilers, so I just read the whole summary on Wikipedia about 100 pages in. If I hadn’t known where it was going, that Fyodor would be murdered halfway through and that Dimitri would be convicted for it near the end, I don’t think I would have stuck with it the whole way through. But knowing where it was leading gave meaning to the early scenes they might not have otherwise had.

Ever read a book or watch a movie that you’ve heard was good but didn’t finish it? I have. And knowing where it’s going, having it “spoiled,” makes the difference. Most of the harm from spoilers is not on how we experience the story, but it’s because we’ve been told we are supposed feel hurt by them that we do. The harm is in our reaction.

Certain parts of online fan culture have creating a moral outrage over spoilers that I know we aren’t going to remove overnight, but there’s a kind of performative over-reacting I think we could stand to do away with soon. And at the last, we don’t have to overreact and be so careful not to reveal the plot of decade-old movies.

And try looking up the end of the next movie you see. You might be surprised by the difference it makes, understood as a whole. Don’t be afraid of spoilers, instead ask what art has to offer other than killing off characters.

Endnotes:

- James Poniewozik, “Dead Tree Alert: Don’t Fear the Spoiler,” Time, 19 July 2012, < http://entertainment.time.com/2012/07/19/dead-tree-alert-dont-fear-the-spoiler/>. ↩︎

- Jonathan Leavitt & Nicholas Christenfeld, “Story Spoilers Don’t Spoil Stories,” Psychological Science 22 (2011): 1152-4. ↩︎

- François Truffaut, Hitchcock (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983): 73. ↩︎