“Toleration,” says Brian Leiter in Why Tolerate Religion?, “may be a virtue, both in individuals and in states, but its selective application to the conscience of only religious believers is not morally defensible.”1 This is, indeed, a bit of a problem for the cause of toleration of religion and conscience, but it is made more difficult by the general conflict between the state and society on one hand and the right to freedom of conscience on the other. It is also complicated by the difficulties of living in a reality where freedom of conscience is often on the retreat and needs to compromise and take little victories where it can.

The most effective practical defense of freedom of conscience of any kind has been the jurisprudence surrounding the “free exercise” clause of the first amendment to the US Constitution. Elsewhere, codes like the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and State, all of which explicitly enumerate a protection of freedom of conscience, were completely ineffective in hindering French law from banning various sacred head coverings in many places, such as schools, including Sikh turbans, Islamic hijab, and Jewish yarmulke.

Keeping in mind the relative efficacy of first amendment protections, which have effectively protected not just religious symbols but even the rights of conscientious objectors, is it morally indefensible to look to freedom of religion as the bulwark, as the jumping-off point, for the defense of freedom of conscience?

There is a crucial reason that freedom of conscience beyond that of religion has so rarely been substantially recognized in any body of jurisprudence: the state is in the business of regulating peoples’ lives. Government force, by its very nature, aims to enforce the dictates of the conscience of the legislator over the conscience of the individual. Freedom of conscience is severely limited in its scope as a general legal principle because the principle of toleration of liberty of conscience, within the bounds of the harm principle, points to a conclusion most would prefer to avoid: in the pursuit of the “general welfare,” the state, and we who act as its indirect legislators by voice and vote, often trample the freedoms we are supposed to protect.

The problem of religious toleration is one for both ethics and law, because it’s the problem of trying to regulate society by legal force that puts the free exercise of individual conscience in jeopardy in the first place. Defenders of freedom of conscience have to act as pragmatic legalists. Leiter asserts that “the best arguments for the moral ideal of toleration would not favor singling out only religion… for special exemptions from generally applicable laws.”2 This, of course, depends on what we mean by “the best arguments.” If we are to say that means the most pure and principled arguments, I’m inclined to agree. If we are to say that means the most effective arguments, that’s rarely the case. When the issue of freedom of conscience is the subject of legal dispute, the best argument for the moral ideal of toleration is to say that it’s the principle enshrined in the first amendment. It’s an annoyingly simple answer but the history of American jurisprudence indicates it’s also the best one.

The historical arguments for religious toleration are typically utilitarian in nature, and argue not from principle, but from a pragmatic assessment of the risks and difficulties of bringing the law into conflict with religion. The writings of John Locke, however, illustrate a crucial point in making a principled stand for freedom of conscience: while principle is the most important thing for those who deal in similar principles, for addressing the greater population of those who might reject your principles, pragmatism is the only tool that might work. Leiter claims that “On one reading of John Locke, his central nonsectarian argument for religious toleration is that the coercive mechanisms of the state are ill-suited to effect a real change in belief… In consequence, says the Lockean, we had better get used to toleration in practice-not because there is some principled or moral reason to permit the heretics to flourish but because the state lacks the right tools to cure them of their heresy.”3

While what Locke’s “central” argument is supposed to be could be up for argument, the only reading of Locke that doesn’t find “some principled or moral reason” for religious toleration is that skips key passages all together. As somewhat of a Lockean myself (at least in political philosophy, I wouldn’t touch his metaphysics with a 10-foot tabula rasa), I include freedom of conscience and freedom of religion within the same category as “liberty” as Locke uses it. Locke believed that the first principle that we must bring to law and politics is the harm principle, that which says its fundamentally wrong to take the life, liberty, or property of another. In libertarian thought this has been usefully encapsulated in the freedom from aggression, or the right not to be aggressed against by another. While I might not be able to speak for all who hold this principle, I believe that even if it is an absolute utilitarian good with no caveats, no possibility of the action backfiring, it is still wrong to murder, enslave, or rob another person – though I would, perhaps, concede the possibility of allowing one wrong to avoid a much greater harm. It’s from the principle that it’s wrong to initiate aggression that I think we should derive the rights of life, liberty, and property.

In actuality, these principles probably came to Locke and many others like him as a result of intuition, but Locke, who didn’t believe in natural intuition, tried to ground the principle of rights in his understanding of natural law: “The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possession”4 Locke uses both “God” and “nature” as the source of these rights, and it’s this principled moral reasoning that the US Declaration of Independence draws on when it claims that all men are “endowed by their Creator” with the rights to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” and that the United States were entitled to independence by “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” This is the principle that Rawls was trying to justify logically with his “veil of ignorance” and his virtue of fairness (and, in my view, failing and making a mess of the issue in the process).

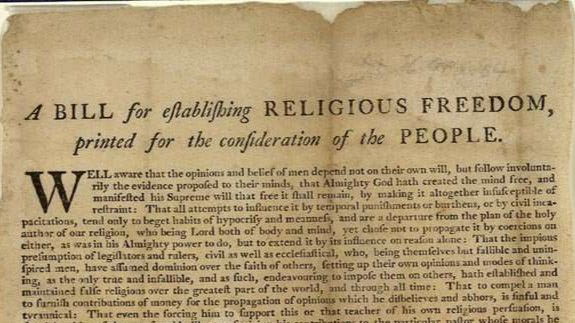

In his First Letter Concerning Toleration, which Leiter’s source draws on, Locke says up front that his “first consideration” is that “it appears not that God has ever given any such authority to one man over another as to compel anyone to his religion.”5 This first principle starts on Locke’s principled approach, but Locke spends most of his space and time on the practical arguments, the kind of arguments that Hobbes and Mill might come up with collectively if they were to work together. This is the result of pragmatism, of acknowledging that even when one believes that rights-based and deontological arguments support a broad freedom of conscience, the constraints of living in a world that disregards rights whenever it’s a matter of convenience sometimes require narrowing that claim to a utilitarian or Hobbesian appeal. I’d like to illustrate this by analogy:

Imagine you were taken hostage by a murderous fanatic but that person was open to conversation as the situation dragged on and you had a good opportunity to try to talk him out of killing you. As I mentioned before, I personally believe all humans have the fundamental right to life, that the base wrongs in the world are aggression against a person’s life, liberty, or property, respectively. But if I were in that hostage situation and my words were the only weapon I had to try to save my own life., I wouldn’t try to convince the potential killer based on any deontological principle. When someone threatens the rights of another, it is generally safe to assume they don’t acknowledge those rights, or else think that those rights don’t apply to their victim. In a situation like that, I would make an appeal based on what the murderous hostage-taker thinks his best interests are. I would try to convince him that killing me would make it less likely for him to escape, or even that letting me go would increase his chances of making it out of this situation alive. But in doing so, I wouldn’t be abjuring my deontological philosophy, I would be acknowledging the realities of living in a world with people who dismiss the rights of others. Similarly, when I find myself defending freedom of speech or the press, I usually have to do so on utilitarian grounds, because I’m arguing with those who don’t believe it is a right, which it is wrong to violate as a deontological matter.

It’s an unfortunate reality that conscience without religion can be crushed more easily by the mechanisms of the state, whether for one person or over the course of generations. Religion is more intractable, the convictions and practices that come with it can outlive the most determined and brutal attempts to suppress them. Government has long been in the business putting the conscience of the legislator over the conscience of a minority, and acknowledging the right to religious toleration represents only an uneasy truce between the two kingdoms. There are a few reasons, beyond the history of relative success of religious claims of conscience, to believe that it is morally defensible to specifically protect those religious claims.

Religion is a broader concept than conscience alone. It systemizes demands of conscience and makes it possible to deal with them as a matter of law. Take the example of the draft. Regarding the draft, religion is a good sorting mechanism for evaluating claims of conscience, where claims of conscience cannot be tested. An individual who claims to be a principled pacifist could actually have seriously taken his readings of Noam Chomsky to heart or he could simply not want to be enslaved by the state, put through brainwashing and intense physical hardships, and possibly killed. There is little evidence a conscientious objector can bring to such an argument, and no sober person would consider the government to be a good judge of someone’s character and sincerity. But if the individual is a Seventh-day Adventist, who has practiced the rigorous tenets of the faith for years, it’s a fairly strong indicator that he is, in fact, sincere.

Leiter disagrees with this argument, saying that it would be better to have no exemptions than to have exemptions be unfairly passed out with preference to the religious over the non-religious. But is it preferable to have injustice be done to all equally than for injustice to be done only to some? When the point has been conceded that government has the right to force men into involuntary servitude, the gross injustice of forcing men into war against their conscience will occur. Wouldn’t it be better to limit that injustice as much as we possibly can? To hold our principles, but also to fight our (rhetorical) battles in reality?

There is, however, a hiccup in the way Leiter has categorized religious claims of conscience within general claims of conscience. While there is overlap, freedom of religion is not a neatly contained sub-category within freedom of conscience. It’s possible that relating the claims of religion and conscience is the product of an oversimplification, as religion deals in faith, not reasons. “At its most basic level, the concept of faith describes the manner in which a particular belief or set of beliefs may be subscribed to by human beings. In that sense of the word, faith exists as a form of rival to reason.”6

A simple demonstration of this is in the right of a condemned prisoner in the United States to be administered to by a representative of their faith. How far this right goes is an ongoing topic of legal dispute, but it must be noted that this is a right not to act according to one’s conscience – the condemned will die either way – but it demonstrates that there is a freedom to religious ritual.

Claims of conscience and claims of religion also differ in that one can be talked out of claims of conscience, insofar as they are based on reason or emotion, but claims of faith are – assuming they are strictly claims of faith – immune from the appeals to reason, empiricism, and compromise. Conscience can be flexible, particularly in the things the law might consider trivial, in a way that religion often cannot. This is not necessarily to say that those acting on religious beliefs are irrational, only that their claims on conscience are a matter of faith. If someone believes that the reserved time for prayer is on Saturday, as do Orthodox Jews, or 5 times a day at proscribed times, as do Muslims, it would do no good to use reason to convince them otherwise. It wouldn’t make sense to present an argument to the Jew that Sunday is a better day for the Sabbath; after all, it’s the day that many businesses are closed and moving the sabbath to a Sunday allows for brief overnight trips in which one leaves on a Friday night and returns on Saturday afternoon. Nor would it make sense to argue to a Muslim that it would be much more convenient for them and everyone else if they moved all five Salah to take place to the evening after the workday. And if we were to make such an argument and the Jew or the Muslim were to laugh in our face, we would be the ones acting foolishly for even attempting to move the dictates of faith with reason.

Nor is it to say that religion is necessarily arrived at irrationally either; centuries of Catholic theologians thought they had obtained strong rational evidence, if not indisputable proof, of their religion. Leiter argues that “it is dubious that these positions are really serious about following the evidence where it leads, as opposed to manipulating it to fit preordained ends.”7 This, of course, is true not only of religious beliefs, but of beliefs in general, though we, as biased humans, are skilled at only seeing the bias of those we disagree with and ignoring our own.

But even if one can arrive at belief in the Roman Catholic religion through reason alone, the commands it holds that God has placed on humanity are still a matter of faith in God. Faith in this sense might be synonymous with trust or confidence that we might have in a mortal leader. Whether or not we gain this kind of faith rationally, this faith refers the tendency to put the judgement of another above our own. People believe in a certain conception of deity for many different reasons, but when they do believe, they have faith that the judgement of the omniscient creator of the universe is above that of humans, no matter how rational anyone thinks human judgement might be.

Leiter throws a twist into the principle-of-harm-based arguments by the case in his book, one which concerns a Sikh boy who the courts ruled could bring his ceremonial knife to school. This does not directly aggress against anyone’s life, but it does theoretically increase the level of risk to life others in that public school face. Leiter ultimately objects to this allowance because of his principle that there should be no exemptions if they would be unfair to non-religious people with only the convictions of conscience. It’s important to note that the task of the government cannot be to eliminate all risk of harm. If it was, it would be derelict in not confining all citizens to a padded cell. Along with the rights of life, liberty, and property is a right to choose one’s level of risk, which is why the traditional approach, in which parents choose a school that most aligns with their values, including even their religious values, is the one that most allows for liberty of conscience to be preserved.

Mill observed that religion is among those things threatened when the “liberty of private life” is being encroached on by “the feeling of the majority.”8Those who would try to control the lives and the actions of others beyond the basic principles of defense from aggression will inevitably trod on the ability of others to act according to the dictates of their own conscience. When that liberty is under threat, its defenders must make the pragmatic, strategic decision of retreating to a bulwark. In American society and jurisprudence, the best bulwark of the freedom of conscience has been, and likely will remain, in the free exercise of religion.

Written June 2022

Endnotes:

- Brian Leiter, Why Tolerate Religion? (Princeton University Press, 2013), 133. ↩︎

- Leiter, 4. ↩︎

- Leiter, 10. ↩︎

- John Locke, Second Treatise of Government (1690; Project Gutenberg, 2003), ch. II, sect. 6, retrieved 16 June 2022, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7370/7370-h/7370-h.htm. ↩︎

- John Locke, “First Letter Concerning Toleration,” trans. William Popple (1689), 7, retrieved 16 June 2022, https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/econ/ugcm/3ll3/locke/toleration.pdf. ↩︎

- Frederick Schauer, Free Speech: A Philosophical Enquiry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 86, quoted in Leiter, 31. ↩︎

- Leiter, 40. ↩︎

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859; Econlib, 2018), ch. IV, retrieved 16 June 2022, https://www.econlib.org/library/Mill/mlLbty.html?chapter_num=4#book-reader. ↩︎