The American Revolution belonged to both the philosophical statesmen and the rural radical reactionaries.

In December of 1763, an armed mob of back-country Pennsylvanian settlers calling themselves the “Paxton Volunteers” massacred two groups of non-combatant Conestoga Indians, most of them women and children, before marching on Philadelphia to “humbly petition” for their political demands, including funding for frontier defense, and possibly to kill more Indians who had taken shelter in the city. They were met by Benjamin Franklin and other local leaders and agreed to disperse on the condition that their demands be presented to the legislature.1

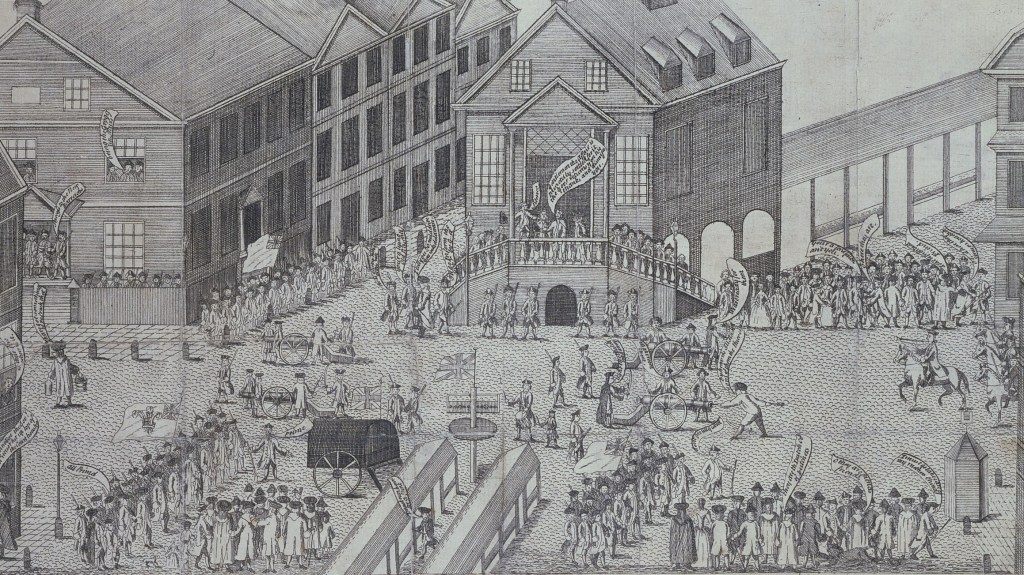

The “Paxton Boys’” declaration of their demands and grievances in “A Declaration and Remonstrance of the Distressed and Bleeding Frontier Inhabitants of the Province of Pennsylvania” and Franklin’s fiery denunciation of the “armed demi-savages” in his pamphlet “A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County” led to an extended “Pamphlet War” between the supporters and opponents of the frontier militia and their agenda.2 The pamphlet war and its rhetoric have been the subject of considerable historical analysis, owing to the quantity and variety of the published work: sixty-three published pamphlets and ten political cartoons, the first political cartoons published in the colonies.3

The Paxton Boys’ violence and accusations against the peaceful Christian Conestoga Indians have rightly been the focus of historical attention on the group, but their grievances with the legislature and government of Pennsylvania and the Indian policy of the colonies in general are notable as well, as they demonstrate a pattern of populist action that would be echoed in the opening year of the future revolution and even in certain subsequent local rebellions. This widening rift between the colonists and their traditional leaders was part of a larger trend leading to the revolution that would break out in just twelve years.

A pamphlet written by an unknown Paxton declares their causes of conflict to “a candid and disinterested world” and might be compared to the Declaration of Independence where the rebels of 1775-1776 declared their grievances against the British “to a candid world.”4 The expression was similarly used in other radical or reactionary writings in which frustrated petitioners formed their complaints as being addressed not to the government they were complaining against, but to the outside world, asserting that their local argument was of worldwide importance.5 This may demonstrate the superior familiarity with recently published satire which historian Alison Olson credits the Paxton Boys’ supporters with possessing, as well as the ability of radical groups to adapt rhetoric for new purposes.6

The Paxon supporters, even while often being critical of the massacres themselves as unfortunate collateral damage, draw on a shared tradition of revolutionary and reactionary rhetoric that was developing among the English colonists of North America. They use similar language, even loosely quoting John Locke, and they followed the same pattern of deciding on action at the militia level and going to battle before formally declaring their grievances, as did the militia in Boston a year before the Declaration of Independence. Many of those who wrote against the Paxtons, including Benjamin Franklin, used similar rhetoric in later writings. The dynamic of this conversation consists of two sides talking past each other: the Paxtons’ supporters writing about their various political grievances with the establishment in Philadelphia, and the Paxton enemies focusing on the brutality of the massacre.

The massacre was precipitated by the fragile position of the residents of rural Western Pennsylvania, where Penn proprietors claimed that the colony stretched from the Delaware river to Lake Erie and the Ohio river, 300 miles to the east. These claims conflicted with the realities of settling the region. The loosely settled frontier barely reached past the Susquehanna, only 100 miles from Philadelphia and the colony’s western boundary at the Delaware. The residents of this border community were largely Scottish or Irish immigrants and had left the British Isles as Presbyterian religious dissidents. Pennsylvania was founded as a Quaker colony, and proprietor William Penn’s religious pacifism had allowed better relations with the Indians than was typical in northern colonies, but his non-Quaker sons John and Thomas were responsible for the “walking purchase” scheme.7 Many Philadelphians remained Quaker and pacifist, but the Church of England and Presbyterian churches were gaining influence there as well, and Thomas Penn himself had converted to Anglicanism. This disconnect between the remote leadership in Philadelphia and the frontier people in the Paxton area would cause similar contention to that which would later occur between the remote Crown and Parliament in England and the people in colonial North America.

The Pennsylvanian legislature had raised no militia before the beginning of the French and Indian war in 1754, and even after the war began, the funding was complicated by the pacifism of the legislators and by the conflict between the appointed Lieutenant Governor and the assembly over the issue of taxing Penn lands to pay for the militia. The end of the war in 1763 and the Royal Proclamation in the same year intended to separate the Indians and colonists to reduce conflict should have been a respite for the beleaguered people of the Pennsylvania frontier, but these events were followed immediately by the war waged against by tribes in the Ohio, Great Lakes, and Illinois areas led by the Odawa war chief Pontiac.8 “Pontiac’s Rebellion” was joined by the Western Delaware and several other tribes in the Ohio area. Pontiac’s allies captured British forts as far east as Ft. Vendago in Western Pennsylvania, about 150 miles from Paxton township. Scots-Irish residents of the Paxton area claimed that Indian raiding parties had killed or kidnapped isolated settlers and that the nearby Consestoga were harboring and giving aid to the Delaware raiders. The “fighting parson” John Elder, leading Presbyterian minister of the area, rallied the volunteer force that would become the Paxton Boys and was appointed as its commander.9

The force was authorized by the Assembly to act only for defensive purposes, but Elder intended to use them to take punitive and pre-emptive actions against Indians.10 In October, Captain Bull of the Eastern Delaware attacked the settlement at Mill Creek, killing ten settlers.11 Frustrated with the perceived lack of support from the provincial government and their inability to track down enemy Indians, the company of Paxton Boys escalated their violence to a new level.

On the morning of 14 December 1763, the Paxton Boys attacked the peaceful Indian town inhabited by the remnants of the Conestoga, burning the town and killing six. The new governor, John Penn, reacted punitively, placing a bounty on the Paxton Boys and attempting to shelter the surviving Conestoga in Lancaster to protect them from both other Indians and their white neighbors.12 The rampaging company of Paxton Boys attacked the town, killing fourteen of the sixteen Indians there, including eight children. Penn’s attempts to discover the identities of the individuals responsible for the massacre from Reverend Elder were unsuccessful, and he soon learned of rumors that 200 Paxton Boys would next come for the Indians on Province Island.13

Penn appointed Benjamin Franklin to oversee a temporary volunteer militia in Philadelphia to meet the Paxton Boys, who reached nearby Germantown on February 5th. Franklin and other Philadelphia leaders met to negotiate with the Paxton Boys in a Germantown tavern on the 7th, and it was there that the Paxtons agreed to disperse on the condition that they be permitted to send a few of their men to confirm that the Indians taking refuge in Philadelphia were not enemies and that their concerns would be heard in their pamphlet.14 The march was over, but the war of words had begun.

The pamphlet written by Matthew Smith and James Gibson on behalf of the Paxton Boys asserted that the murdered Indians were enemies, and that “it is contrary to the Maxims of good Policy and extremely dangerous to our Frontiers, to suffer any Indians of what Tribe soever, to live within in the inhabited Parts of this Province, while we are engaged in an Indian War…”15 Franklin wrote his pamphlet condemning the Paxton Boys before their march on Philadelphia, describing the victims and the brutality of the raid, including a pre-emptive sarcastic retort that “should any Man, with a freckled Face and red Hair, kill a Wife or Child of mine, it would be right for me to revenge it, by killing all the freckled red haired Men, Women, and Children.”16

Historian Judith Ridner suggests that this satirical assertion was intended as a challenge to Irish Presbyterians increasing influence on Pennsylvanian political life.17 The changing demographics of Pennsylvania were already tipping against the pacifist Quakers and the dominance of the Penn proprietary system, and the Paxton Boys claimed that the massacre would have been unnecessary if they had been allowed to represent themselves properly: “Can they who had it in their Power to remove this Complaint be Friends to Liberty, while they can deliberately persevere in such a nortorious Violation of our Charter & such a scandalous Encroachment on so important a Privilege as being equally represented in Legislation?”18

Economic historian Murray Rothbard points out that this discrepancy is a common contention between older, established populations and areas with new populations.19 This contention was not unlike that which would be raised by the supporters of the revolution twelve years later. On the eve of the revolution the newer territories of the British Empire, i.e. the North American colonies, were not represented at all in the Parliament. This legislature governed both them and the older territories in Great Britain, yet only those British citizens living and holding land in Britain were represented. Here again, we see that the Paxtons focused their criticism on similar political grievances to those that the Continental Congress would focus on later, even if their underlying motives could be quite different.

But the motives of the rural Paxtons and the supporters of the American Revolution were not entirely different. Despite his angry condemnation of the Paxton Boys and the massacres, Benjamin Franklin was not their opposite on issues of Indian policy. He was not a Quaker pacifist, and he was not particularly interested in William Penn’s old approach of giving gifts to and appeasing the Indians. As he asserted in a letter written less than a year before the massacres: “We stoop’d too much in begging the last peace of them [Indians]; which has made them vain and insolent; and we should never mention peace to them again till we have given them some severe blows and made them feel some ill consequences of breaking with us.”20

A Paxton supporter calling himself a “True Countryman” said in a pamphlet that the Paxton Boys’ “demands were far too reasonable to be rejected, they were Gentle and easy, not father then Pointing out to the Government such of these Savages had been guilty of Murder, and a praying likewise that the Government would take notice, and try them by the Laws of the Place accordingly; they had no Intent in the least to molest Man, Woman, and Child. Their Grievance as it is said were yet somewhat farther; they had paid for Lands, paid also their Taxes, serv’d his Majesty, and all were in a Manner taken from them; indeed some went so far as to say, that it was given to Savage Indians, who were at this Time rioting in all the Plenty that so great and Fertile a Province could afford”21 He similarly objected to the appeasement and gift-giving approach to Indian policy that William Penn had initiated and that John Penn was continuing, albeit with less ambition or success.

The Declaration of the Paxton Boys includes several issues unrelated to Indian policy and defense, including a protest that the right to a trial by jury of one’s peers was under threat: “We understand that a Bill is now before the House of Assembly, wherein it is Provided, that such Personas as shall be charges with killing any Indians in Lancaster County, shall not be tried in the County where the Fact was committed, but in the Counties of Philadelphia, Chester, or Bucks. This is manifestly to deprive British Subjects of their known Privileges…”22 The law was passed by the legislature with the intent of preventing a Paxton-sympathetic jury composed of their neighbors in Lancaster County from acquitting the murderers should they be brought to trial. The law was never used to convict anyone as none of the Paxton Boys was ever brought to trial, but this fear of encroachment on jury trials by a distant government where the frontier’s lacked representation has a lot in common with a concern that would later be articulated by the Second Continental Congress in the Declaration of Independence: “the present King of Great Britain… has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: …for transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences.”23 On the eve of the revolution the perception of the crown undermining the jury system was a concern throughout the colonies in general, and in neighboring New York in particular.24 It was on a smaller scale, but the threat of being taken Philadelphia to stand trial was the rural Pennsylvanian’s equivalent of the New Yorker’s fear being shipped to London for trial.

The rhetoric of the Paxton Boys evokes the philosophy of “well known Laws of the British Nation, in a point whereon Life, Liberty, and Security essentially depend…”25 These were similar the list of rights that Benjamin Franklin and the others at the Second Continental Congress signed their names to assert in 1776, with the replacement of “security” with “pursuit of happiness.”26 This language is drawn from shared sources in the writings of John Locke, who in Two Treateses of Government asserts that man is born with the freedom to preserve his “life, liberty, and estate, against the injuries and attempts of other men” and in A Letter Concerning Toleration speaks of threats to “liberty, goods, or life.”27

It therefore seems likely that Franklin’s furious condemnation of the Paxton Boys and his focus on their crime rather than their grievances and political agenda was the need to distance himself and his agenda from them, in addition to his genuine moral outrage. It is often politically necessary for the moderates to distance themselves from the radical positions taken by the fringe groups that share certain policies and philosophies with them, while those on the fringe try to appeal to the moderates by emphasizing those areas where their agendas coincide.

Historian Alison Olson credits the Presbyterians gaining the upper hand in the dispute despite the brutality associated with the Paxton Boys to “the failure of the Quaker sympathizers to utilize satire as effectively as their opponents.”28 The rhetoric of the Paxton Boys and their supporters is aimed at focusing attention on their grievances and on the entrenched Quaker and Penn establishment, which was already on the wane. But more than this, we can see that the two sides of the argument are failing to listen to each other. The attempts of Paxton sympathizers to justify the massacres themselves are few and brief, while their focus on the contextual events which led, though not inevitably, are expanded on extensively and often left unaddressed by their opponents. When the Quakers and their supporters talked about the brutality of the massacres, their opponents talked about old political grievances, only talking of and trying to justify the violence occasionally, without much success: “In what Nation under the Sun was it ever the Custom, that when a neighboring Nation took up Arms, not an individual of the Nation should be touched, but only the persons that offered Hostilities? who ever proclaimed War with a part of a Nation, and not with the Whole?”29 A sarcastic pamphleteer retorted that the Paxton Boys “bravely conquer’d, our Eye not pitying, nor our Hand sparing either Age or Sex; exulting, as one of our modern Poets says, in the Window’s Wail, the Virgin’s Shriek, and Infant’s trembling Cry.”30

This anonymous pamphleteer said that the Paxton Boys were guilty of “either not knowing, or not distinguishing, between Savage Indians, Heathen Indians, and Christian Indians.”31 When the Declaration of Independence accuses the King of pursuing an Indian policy dangerous to the colonial frontier, it makes this same distinction between “Savage” and other Indians: “He has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”32

The inadequacy of the Pennsylvanian model of government and its entrenched Quaker leadership was blamed by the Paxton sympathizers for the inadequate defensive preparation on the frontier and the resulting need to delegate the defense to an untrained, undisciplined, and poorly armed militia:

When we applied to the Government for Relief, that far greater part of our Assembly were Quakers, some of whom made light of our Sufferings & plead Conscience, so that they could neither take Arms in Defense of themselves or their Country, nor form a Militia Law to oblige the Inhabitants to arm, nor even grant the King any money to enable his loyal Subjects in the Province to reduce the common Enemy. If they were conscientious in this matter, & found that it was inconsistent with their Principles to govern in a Time of War, why did they not resign their Seats to those who had no Scruples of this Kind?33

Though the Presbyterians blamed the lack of military preparedness by the Pennsylvania Government on the pacifism of the Quakers in the legislature, it was in fact the unwillingness of the legislature and the Lieutenant Governor appointed by John Penn to compromise on the issue of taxing Penn family lands to fund the militia that caused their unpreparedness. This had been an issue at the beginning of the French and Indian war back in 1754, and again in responding to the renewed Indian uprisings in 1763. The general assembly of Pennsylvania wanted to tax lands in the colony to pay for the arming and training of the militia, but the Penn family insisted that their proprietary lands were exempt from taxes. The Governor would veto any legislation that would tax the Penns but the legislature refused to fund the militia without it. This deadlock led to disastrous delays in funding the militias until the John Penn promised to pay his share of the tax as a gift.34

With the issues of representation, the Penn controlled executive, and chronic political deadlock, many Pennsylvanians shared the Paxton Boys’ opposition to the proprietary chartered system of government, including Benjamin Franklin, who wanted to see it replaced with a royal colony.35

Henry Muhlenberg, a Lutheran minister in Germantown, believed that the reason the Germans living near Philadelphia did not drive the Paxton Boys out by force was that they sympathized with the grievances they were marching for, including the objection to the proprietary government controlled by Anglican Penns and Quaker legislators, while they generally disapproved of Paxton methods.36 It was in the aftermath of the pamphlet war that an newly elected assembly voted to send Franklin on a mission to England to request a royal colony to replace the proprietary government.37

The Paxton Boys and the Second Continental Congress both followed up military action with “humble petitions” for redress of grievances. The indiscriminate murder of the Conestoga is not comparable with the battles fought by the continental militia against the British, but it does show the pattern to be repeated in many colonial uprisings of the declarations of principles being codified after the uprisings have already begun.

The dispute between the backcountry “Paxton Boys” and their colonial leaders was part of a larger emergence of a form of factionalism that would set colonists against the imperially sanctioned governments that would increasingly undermine the empire in the following years.38 The American Revolution belonged to both the philosophical statesmen and the rural radical reactionaries. The writings of the pamphleteers demonstrate the commonality of the agendas of the “country rabble” and the rest of the colonists and how popular movements within the colonies formed and articulated the ideas of revolution.

Written December 2019

Endnotes:

- Kevin Kenny, Peaceable Kingdom Lost (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009): 161-162. ↩︎

- “A Declaration and Remonstrance,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 99; “A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 59. ↩︎

- Alison Olson, “The Pamphlet War over the Paxton Boys,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 123, no. ½ (1999): 31. ↩︎

- “The Apology of the Paxton Volunteers addressed to the candid & impartial World,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 185; Thomas Jefferson, et al, “Declaration of Independence” (4 July 1776). ↩︎

- Philalethes, “A genuine account of the P-‘s Escape,” The Scots Magazine 11 (1749): 639; Edward Lewis, Oxford Honesty; or a Case of Conscience humbly put to the Worshipful and Reverent Vice-Chancellor, The Heads of Houses, The Fellows &c. of the University of Oxford (London: M. Cooper, 1750): 5. ↩︎

- Olson, Pamphlet War, 32. ↩︎

- Steven Craig Harper, Promised Land: Penn’s Holy Experiment, The Walking Purchase, and the Dispossession of Delawares, 1600-1763 (Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press, 2006): 34-41, 86-87. ↩︎

- Colin G. Calloway: The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006): 74-76. ↩︎

- George W. Franz, Paxton: A Study of Community Structure and Mobility in the Colonial Pennsylvania Backcountry (Outstanding Studies in Early American History, Princeton University) (New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1989): 48-62. ↩︎

- Kenny, Peaceable Kingdom Lost, 125. ↩︎

- Ibid, 129. ↩︎

- Jane T. Merritt, At the Crossroads: Indians & Empires on a Mid-Atlantic Frontier (Williamsburg: University of North Carolina Press, 2003): 287. ↩︎

- Franz, Paxton, 68-73. ↩︎

- Kenny, Peaceable Kingdom Lost, 159-162. ↩︎

- “A Declaration and Remonstrance,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 108. ↩︎

- “A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 63. ↩︎

- Judith Ridner, “Unmasking the Paxton Boys: The Material Culture of the Pamphlet War,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 14, no. 2 (2016): 355. ↩︎

- “The Apology of the Paxton Volunteers addressed to the candid & impartial World,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 188. ↩︎

- Murray Rothbard, Conceived in Liberty (1979; repr., Auburn: Mises Institute, 2011): 572. ↩︎

- Letter From Benjamin Franklin to Richard Jackson, 27 June 1763 (https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-10-02-0158). ↩︎

- “An Historical Account of the late Disturbance between the Inhabitants of the Back Settlements of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphians,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 128. ↩︎

- “A Declaration and Remonstrance,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 105. ↩︎

- Thomas Jefferson, et al, “Declaration of Independence” (4 July 1776). ↩︎

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1967): 108. ↩︎

- “A Declaration and Remonstrance,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 105-106. ↩︎

- Thomas Jefferson, et al, “Declaration of Independence” (4 July 1776). ↩︎

- John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (1689; repr., Dublin: J. Sheppard and G. Nugent, 1774): 216; John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689; repr., Huddersfield: J. Brook, 1796): 26. ↩︎

- Olson, Pamphlet War, 32. ↩︎

- “A Declaration and Remonstrance,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 107. ↩︎

- “A Dialogue Containing some Reflections on the late Declaration and Remonstrance Of the Back-Inhabitants of the Province of Pennsylvania,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 114. ↩︎

- Ibid, 119. ↩︎

- Thomas Jefferson, et al, “Declaration of Independence” (4 July 1776). ↩︎

- “The Apology of the Paxton Volunteers addressed to the candid & impartial World,” in The Paxton Papers (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1957): 187. ↩︎

- This gift was “to be paid out of our Arrears of Quit-Rents,” bad debts owed to the Penns which the Assembly was to collect. See Kenny, Peaceable Kingdom Lost, 78. ↩︎

- Ibid, 7. ↩︎

- Ibid, 159. ↩︎

- Joseph E. Illick, Colonial Pennsylvania-A History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1976): 245. ↩︎

- Merritt, Crossroads, 6. ↩︎